- Research

- Open access

- Published:

Factors associated with posttraumatic stress and anxiety among the parents of babies admitted to neonatal care: a systematic review

BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth volume 24, Article number: 352 (2024)

Abstract

Background

Posttraumatic stress (PTS) and anxiety are common mental health problems among parents of babies admitted to a neonatal unit (NNU). This review aimed to identify sociodemographic, pregnancy and birth, and psychological factors associated with PTS and anxiety in this population.

Method

Studies published up to December 2022 were retrieved by searching Medline, Embase, PsychoINFO, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health electronic databases. The modified Newcastle–Ottawa Scale for cohort and cross-sectional studies was used to assess the methodological quality of included studies. This review was pre-registered in PROSPERO (CRD42021270526).

Results

Forty-nine studies involving 8,447 parents were included; 18 studies examined factors for PTS, 24 for anxiety and 7 for both. Only one study of anxiety factors was deemed to be of good quality. Studies generally included a small sample size and were methodologically heterogeneous. Pooling of data was not feasible. Previous history of mental health problems (four studies) and parental perception of more severe infant illness (five studies) were associated with increased risk of PTS, and had the strongest evidence. Shorter gestational age (≤ 33 weeks) was associated with an increased risk of anxiety (three studies) and very low birth weight (< 1000g) was associated with an increased risk of both PTS and anxiety (one study). Stress related to the NNU environment was associated with both PTS (one study) and anxiety (two studies), and limited data suggested that early engagement in infant’s care (one study), efficient parent-staff communication (one study), adequate social support (two studies) and positive coping mechanisms (one study) may be protective factors for both PTS and anxiety. Perinatal anxiety, depression and PTS were all highly comorbid conditions (as with the general population) and the existence of one mental health condition was a risk factor for others.

Conclusion

Heterogeneity limits the interpretation of findings. Until clearer evidence is available on which parents are most at risk, good communication with parents and universal screening of PTS and anxiety for all parents whose babies are admitted to NNU is needed to identify those parents who may benefit most from mental health interventions.

Background

Having a baby admitted to a neonatal unit (NNU) can be highly distressing for parents [1, 2] and many experience mental health problems during and beyond their baby’s admission [3,4,5]. Evidence from a recent systematic review [5] estimated prevalence of anxiety among parents of babies admitted to NNU was as high as 42% during the first month after birth and remained high at 26% from one month to one year after birth. The prevalence of symptoms of posttraumatic stress (PTS) was equally high at 40% during the first month after birth, 25% from one month to one year and remained high at 27% more than one year after birth.

Unaddressed perinatal mental health problems can have long-term implications for parents, babies and families [6]. Identifying parents who are at risk of developing mental health problems during this vulnerable time is therefore vital so that timely support and interventions can be delivered [7]. However, it is unclear why some parents are more susceptible to develop mental health problems and others are more resilient. In the UK, women are asked about their emotional wellbeing routinely at each antenatal and postnatal contact with healthcare professionals [8]. For women in the general perinatal population, a number of factors are associated with perinatal anxiety. Obstetric factors include current or previous pregnancy complications, surgical obstetric interventions, and miscarriages; health and social factors include a history of mental health problems, domestic violence, being a single parent, having a poor couple relationship or inadequate social support [9,10,11,12]. PTS is associated with traumatic birth events including changes to birth plan, birth before arrival to hospital, emergency caesarean birth, instrumental vaginal birth, and manual removal of the placenta; third and fourth-degree perineal tears are additional risk factors for PTS after birth [13, 14]. The experience of childbirth in and of itself is an independent factor associated with PTS and therefore preterm birth and neonatal complications are considered as add-on stressors [15].

The factors associated with developing postnatal mental health problems in parents of babies admitted to NNU have received comparatively little attention and are poorly understood. It is unclear whether the factors associated with increased risk of mental health problems in the general perinatal population are applicable to parents of babies admitted to NNU, or whether there are different or additional factors for this population. Factors such as the unexpected nature of many NNU admissions, separation from the newborn, and concern about the infant’s health make the experience of parents with babies receiving neonatal care different from that of other parents. Therefore, it is important to understand the risk and protective factors for this specific population to ensure that approaches for assessment, detection and intervention for perinatal mental health problems are optimally delivered and, if necessary, appropriately tailored.

The aim of the review was to systematically collate, appraise and synthesise the current evidence on risk and protective factors for developing PTS and anxiety in parents of babies admitted to NNU.

Methods

Operational definitions

There is no formal or internationally agreed definition of NNUs. The UK Department of Health and Social Care’s definition includes special care units (SCUs), local neonatal units (LNUs) and neonatal intensive care units (NICUs) [16]. The American Academy of Paediatrics’ definition of NNUs include basic care (level I), specialty care (level II), and subspecialty intensive care (level III, level IV) [17]. Within the context of this review we included studies on parents of babies admitted to any level of NNU.

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders Fifth Edition (DSM-5) [18] defines anxiety disorders as disorders that share features of excessive fear and anxiety and related behavioural disturbance. PTS is associated with exposure to trauma. Acute Stress Disorder (ASD) occurs within four weeks of a traumatic event, while Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) occurs when symptoms persist beyond one month. Throughout this review, the term ‘PTS’ is used to cover clinically significant ASD, PTSD or PTS symptoms and the term ‘anxiety’ is used to cover both clinically significant anxiety symptoms or disorders.

The review protocol was prospectively registered with PROSPERO (CRD42021270526) and reporting followed Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guideline [19].

Eligibility criteria

Studies published in any language which examined the potential association of at least one risk factor with PTS or anxiety and were conducted with parents (mothers, fathers and carers) of babies admitted to any level of a NNU in all countries were included. Studies focusing on specific groups such as parents with existing mental health conditions or parents of deceased babies were also considered for inclusion. All observational study designs were eligible.

Search strategy and selection criteria

A comprehensive search strategy was developed and tested using a combination of free-text (title/abstract) keywords and MeSH subject terms to describe the key concepts of PTS/anxiety, parents and NNUs. The search covered the period from the inception of each database until December 2022. No restriction was applied to the electronic searches. The following databases were searched: Medline, Embase, PsychoINFO, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health literature, Web of Science, ResearchGate and Google Scholar; Grey literature was also searched including Ethos, Proquest Dissertations & Theses and OpenGREY. The reference lists of all included studies were also searched for additional eligible studies. The search strategy applied in Medline is shown in Appendix 1.

Study selection and data extraction

All screening of titles, abstracts and full texts was conducted in Covidence [20]. A data extraction form was piloted on selected studies and was then employed for the remaining studies. Data on country, study design, aims, inclusion/exclusion criteria, characteristics of included parents and babies, PTS/anxiety measuring tools, assessment time, potential risk and protective factors relevant to PTS and anxiety, data analysis method and estimated effects for each risk factor were extracted. All screening and data extraction were independently performed by at least two reviewers (RM, VP, SH, FA). Any discrepancies were discussed and resolved by a third author (FA, SH). Authors were contacted when required information was missing or when full texts were not available (N = 16).

Risk of bias assessment

The quality and certainty of evidence were assessed using a modified version of the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale [21]. The modified tool contains seven domains of bias relating to the following sources: selection, sampling, measurement of factors/outcome, analysis, selective reporting and attrition. Low, high or unclear risk rating was used to assess the potential bias for each domain.

Data synthesis

Summary statistics were extracted from all studies, including number of participants, number of risk factors and data relevant to each risk factor identified. When results from univariable and multivariable analyses were reported, only the latter were extracted. Meta-analyses by exposures/risk factors were not feasible due to the variability in the measurement of similar risk factors across studies (e.g. type of measurement tool, cut-off point, categorical or continuous data). Therefore, results were narratively synthesized and reported for PTS and anxiety separately.

Results

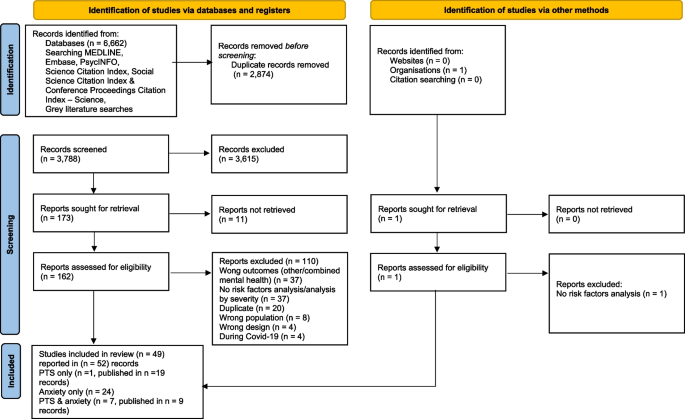

A total of 6,662 records were identified and, after removing duplicates, 3,788 records were screened, of which 3,615 records were excluded. 162 reports were assessed for full-text eligibility (11 reports could not be retrieved) and, of these, 110 reports were excluded with reasons and 49 studies, published in 52 records, were included. 18 studies, published in 19 records, reported on factors associated with PTS, 24 studies on anxiety and 7 studies, published in 9 records, reported on both, see Fig. 1.

Post-traumatic stress (PTS)

Description of the included studies

Table 1 presents the 25 studies published in 28 records [22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49] for PTS (including 7 studies reporting both PTS and anxiety). More than half of the studies were conducted in the USA [22, 25, 27,28,29,30,31, 34, 35, 41, 42, 44,45,46,47], five in Europe, published in six records [23, 26, 36, 37, 48, 49] two in Canada [32, 43], and one in each of the following countries: Australia [39], Argentina [40], Iran [38], South Korea [50] and Taiwan [24]. Six studies [24, 25, 27, 41, 44, 47] were of a cross-sectional design and the remaining studies were cohort studies.

Two studies included bereaved parents of babies who had been admitted to NNU [25, 30] and one study [22] focused entirely on military families. Both parents were included in ten studies, published in 11 records [22, 25, 30, 34, 35, 38, 39, 42, 46,47,48] and only mothers were enrolled in the remaining studies. Gestational age (GA) of the infant was an inclusion criterion in nine studies published in ten records [23, 24, 26, 32, 36,37,38,39, 43, 45], and birth weight (BW) was a criterion in two studies published in three records [28, 29, 31]. Two studies included both GA and BW in their inclusion criteria [27, 40]. All studies used standardised self-report scales.

Risk of bias assessment

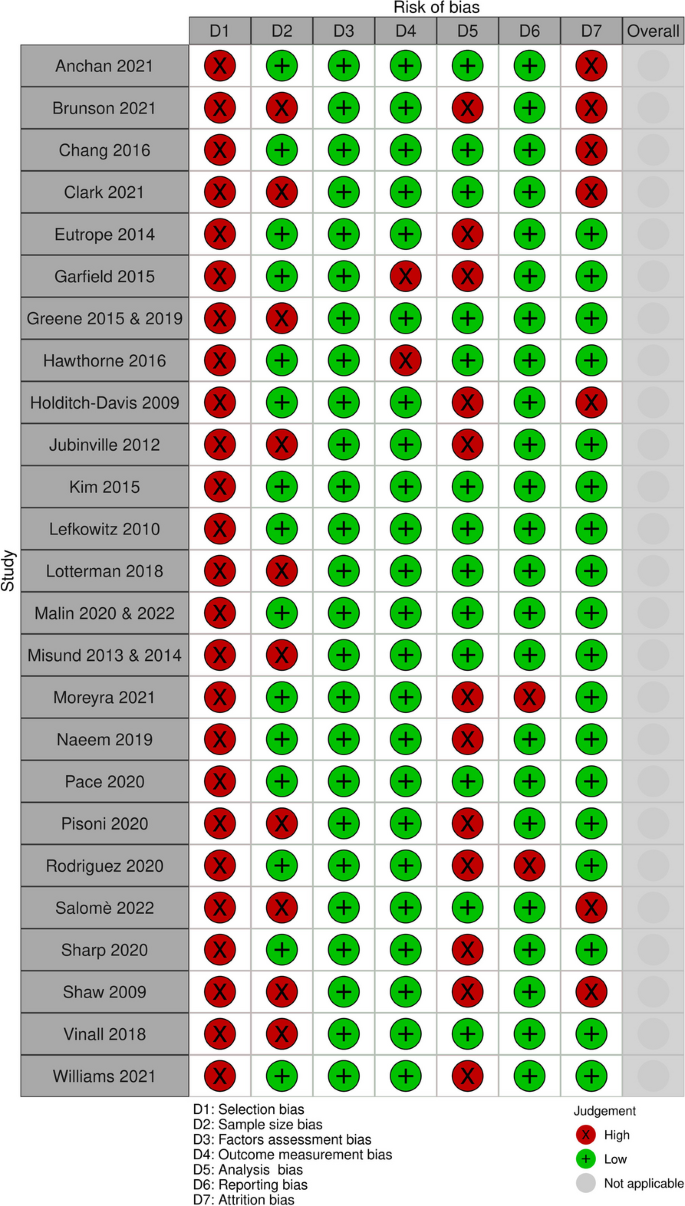

None of the included studies were at low risk of bias across all domains (see Fig. 2- A summary of risk of bias of PTS studies and Appendix 2). All studies had high risk of selection bias because all applied some exclusion criteria and most used convenience sampling. Ten studies, published in 12 records [23, 25, 28, 29, 32, 36, 37, 42, 43, 45, 48, 49], did not employ adequately powered sample sizes. Twelve studies [23, 26, 27, 31, 32, 38, 40,41,42, 44, 47, 49] had high risk of analysis bias due to unmeasured confounding factors or correlational analysis only, and seven studies [22,23,24,25, 31, 42, 47] had high risk of attrition bias due to low participation rates or high loss to follow-up. All except two studies [40, 47] had low risk of reporting bias. All studies were at low risk of bias for factor and outcome measurement.

Factors associated with post-traumatic stress (PTS)

Overall, 2,506 parents were involved across the 25 included studies with sample sizes ranging from 29 to 245 participants. A total of 62 potential risk or protective factors were identified. The factors are detailed in Table 2, presented in a mapping diagram in Table 3 and summarised here under the following eight categories: parent demographic factors; pregnancy and birth factors; infant demographic factors; infant health factors; parent history of mental health symptoms; parent postnatal psychological factors; parent stress and coping, and other factors.

-

1) Parent demographic factors (Ten factors: age, education, sex, ethnicity, parents’ area deprivation, income, employment status, housing and access to transport, single parent, family social risk)

The association between parental age and PTS symptoms was explored in nine studies, published in ten records [23, 27, 29, 33, 34, 36, 37, 40, 43, 46]. Older mothers had significantly higher PTS scores at two weeks post NNU admission in one study of only 29 mothers, reported in two records [36, 37]. In the remaining studies there was no significant association between parental age and PTS symptoms. Seven studies [23, 25, 27, 33, 40, 43, 46] explored the association between parental education and PTS symptoms. Lower education was associated with more PTS symptoms in three studies [25, 40, 43] and consistent with this finding, one study [43] found mothers with more years of education had fewer PTS symptoms at discharge. Similarly, in another study [40], mothers who had a lower education level accounted for significantly more cases of PTS at 6–36 months after birth. Additionally, among bereaved mothers [25], higher education level was associated with fewer PTS symptoms even three to five years after the baby’s death. The remaining four studies found no association between parental education and PTS symptoms. The association between sex of parent and PTS symptoms was explored in seven studies [22, 25, 34, 38, 39, 42, 47]. Three studies [34, 38, 39] provided data at multiple time points. Two studies [38, 47] found PTS symptoms were significantly more prevalent in mothers than fathers while their babies were still in NNU and a month later [38]. Evidence from the remaining five studies showed no association between sex of parent and PTS symptoms. Three studies [34, 46, 47] explored the association between parental ethnicity and PTS symptoms, and none found any association during NNU stay [34, 47] or at three months post NNU discharge [46]. However, in one of the studies [34], only 28% of participants were from minority backgrounds. The association between parents’ area deprivation and PTS was explored in one study [29], and mothers residing in poorer neighbourhoods had lower PTS scores at birth than those residing in more privileged neighbourhoods, but this association disappeared at one year. Housing and access to transport were not associated with PTS symptoms at three months post NNU discharge in one study [46]. In bereaved parents [25], a lower family income for fathers, but not for mothers, was significantly associated with more PTS symptoms at three months to five years after the baby’s death. Two studies [38, 46] explored the association between employment status and PTS symptoms. One study [46] found employment status was not associated with PTS symptoms after birth, yet the other study [38] found PTS symptoms were significantly greater among employed mothers and mothers with unemployed partners one month after the birth [38]. One study [35] found no significant association between being a single parent and PTS symptoms three months after NNU discharge. One study [39] explored family social risk, a composite of family structure, education, occupation, employment, language spoken and maternal age, and found no association with PTS symptoms in parents of very preterm infants at 12 and 24 months corrected age.

-

2) Pregnancy and birth factors (Seven factors: parity, multiple pregnancy, mode of birth, pre-eclampsia, threatened preterm labour, in-vitro fertilisation, traumatic childbirth)

Three studies [23, 28, 33] explored the association between parity and PTS symptoms. Two of the studies [28] found primiparity was a significant risk factor for elevated PTS symptoms during NNU [25] and at one year corrected age [33] and the third study [23] found no significant association between parity and PTS symptoms 18 months after birth. Multiple pregnancy was explored in three studies [23, 33, 39] and giving birth to twins was not associated with PTS symptoms in any study assessed at one year or later. The association between mode of birth and PTS symptoms was explored in two studies, reported in three records [23, 36, 37]. One study, reported in two records (2013, 2014), found planned caesarean section compared to normal birth was associated with lower PTS symptom scores at two weeks post NNU admission. However the other study [23] found caesarean section (planned and unplanned) was not significantly associated with PTS symptoms at 18 months, yet there were more caesarean sections among the group of mothers who experienced PTS symptoms during the study. Seventy-five percent required a caesarean section compared to 47.4% in the group with no significant PTS symptoms. Preeclampsia was significantly associated with higher PTS scores at two weeks post NNU admission in one study, reported in two records [36, 37]. A history of threatened preterm labour was explored in one study [23] and was not associated with PTS symptoms at 18 months after birth. In vitro fertilization [23] and traumatic childbirth [41] were each explored in one study and were not found to be associated with PTS symptoms at one to four months and 12 months after birth, respectively.

-

3) Infant demographic factors (Five factors: gestational age, birth weight, Apgar score, sex of infant, age at infant)

Seven studies [22, 23, 33, 40, 42, 43, 46] explored the association between gestational age (GA) and PTS symptoms. Only two studies [23, 40] found a significant association between GA and PTS symptoms. One study [23], where GA ≤ 32 weeks was an inclusion criterion, found that infants born to mothers with elevated PTS scores 18 months after birth had a lower GA age by almost one week, and one study [40] found a significantly higher frequency of infants born ≤ 28 weeks gestation among mothers with more PTS symptoms 6 to > 36 months after birth. The association between birth weight (BW) and PTS symptoms was explored in five studies, [23, 26, 29, 40, 42]. Increased infant’s BW was significantly correlated with lower PTS symptoms during NNU stay [26] and lower PTS score at birth, but not at 12 months later [29]. PTS symptoms were more prevalent at six to > 36 months among mothers to a very low BW (< 1000 g) infant [40]. Two other studies [23, 42] reported no significant association between BW and PTS symptoms at four and 18 months after birth, respectively. The association between Apgar score and PTS symptoms was explored in four studies [23, 33, 42, 44] and only one study [44] found Apgar scores (1 min, 5 min) and PTS symptoms were negatively correlated during NNU admission. Two studies explored sex of infant and PTS symptoms and found no association at NNU discharge [43] or 18 months after birth [23]. One study explored age of infant and PTS symptoms at 7–24 months vs 25 to > 36 months and found no association [40].

-

4) Infant health and care factors (17 factors: clinicians’ perception of infant health, parents’ perception of infant health, mother-infant contact, length of NNU stay, mother-infant relationship, mother-nurse relationships, hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy (HIE), ventilation, severe bronchopulmonary dysplasia, vasopressor, hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy (HIE), palliative care consultation, seizures, invasive procedures, number of medical interventions, infant general development, re-hospitalisation and emergency visit.

Nine studies reported on clinicians’ perception of infant health [23, 25,26,27, 34, 35, 40, 44, 49]. Three studies [23, 26, 49] used the Perinatal Risk Inventory (PERI) scale [51] to assess clinicians’ perceived risk of adverse infant outcomes. One study [26] found a significant correlation between PRI score and parental PTS symptoms during NNU, one study found a significant correlation during NNU admission but not 12 months later [49], and one study found no association at 18 months corrected age [23]. One study used the Neonatal Acute Physiology-Perinatal Extension- II (SNAPPE-II) [44], a tool for predicting outcomes in critically ill newborns, and found a significant correlation between SNAPPE-II scores and PTS symptoms during NNU admission. Four studies [25, 34, 35, 40] used non-standardised clinical indicators to assess clinicians’ perception of the baby’s health but only one study reported a significant association. In one study [40], severe neonatal morbidity was significantly more common among mothers with elevated PTS score 6—> 36 months after birth. However, the Neurobiologic Risk Score (NBRS) [52] which assesses baby’s neurological insults was not significantly correlated with PTS scores three months after birth [27].

The association between parents’ perception of infant health and PTS symptoms was assessed in five studies, published in six records [22, 25, 35, 44,45,46], and all studies reported a significant association. Parents who appraised their infant’s health as “sick/severe” were almost four times more likely to report PTS symptoms in two studies, one at 1–2 months [22] and one at three months post NNU discharge [35]. Also in [46], parents’ uncertainty about infant’s health was significantly associated with higher PTS scores during NNU and at three months post discharge. Among parents of deceased babies [25], mothers’ perception of infants’ symptoms and fathers’ perception of infants’ suffering were associated with increased PTS scores even three to five years following infant death. One study found a significant correlation between subjective infant health and more PTS symptoms during NICU admission [44] and one study found that a higher number of health problems reported by the mother was associated with higher PTS scores six months after birth [45]. Neither mother-infant contact (verbal and physical contact rated on a five-point Likert scale) while in NNU nor the number of NNU visits per week were associated with PTS symptoms at six months [45]. Additionally, mother-infant relationship assessed by CARE-index [53], which measures the interaction patterns between infants and carers, was not associated with more PTS symptoms during NNU stay or at 12 months corrected age [49]. One study explored mother-nurse relationships at six months [ref],based on nurses rating mothers’ understanding of explanations relating to infants’ care and health (,and found no association with PTS scores.

Length of stay in NNU was explored in seven studies [34, 40,41,42,43, 45, 46] and only one study [43] adjusted for GA. Three studies [34, 45, 46] found significant, albeit contradictory, associations between length of NNU stay and PTS symptoms. One study [34] found longer length of stay was correlated with lower PTS scores during NNU admission and two studies [45, 46] found longer length of stay was associated with higher PTS scores at three months [46] and six months [45]. Low grade intraventricular haemorrhage (IVH) was significantly associated with higher PTS scores 2 weeks after NNU admission in one small study, reported in two records [36, 37]. Requiring ventilation for > 30 days, severe bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) and vasopressors support were all more prevalent among parents who reported PTS at three months post NNU discharge [46] in one study. Parents of infants exposed to a greater number of invasive procedures had significantly more PTS symptoms during NNU in one study [43] which adjusted for GA. Conversely, another study [25] found number of medical interventions was not significantly associated with PTS symptoms 3 months to 5 years after infant death. Hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy (HIE), palliative care consultation and seizures were not associated with PTS scores in one study [46]. One study explored infant’s general development [49] and one study explored rehospitalisation or emergency visits [33]; neither were found to be significantly associated with PTS symptoms.

-

5) Parental history of mental health/trauma factors (Four factors: parental history of mental health problems, family history of mental health problems, previous traumatic events, traumatic childbirth).

Three studies reported on parental history of mental health problems [22, 45, 46] and all found significant associations. One study [22] found a significant association with a positive screening of PTS two weeks after birth, one study found an association during NNU [45] and at three months post NNU discharge [46]. One study found [45] previous mental health problems in addition to low mother-infant contact (physical or verbal) was significantly associated with higher PTS scores during NICU admission. Two studies [34, 46] reported a significant association between family history of depression/mental health problems and PTS symptoms during NNU admission [34] and at three months post discharge [46]. Previous traumatic events (physical or psychological e.g. car accident, unexpected death of loved ones and sexual assaults) were assessed in three studies, published in four records [28, 29, 38, 41] with mixed results. One study, published in two records [28, 29], found exposure to previous traumatic events was associated with increased PTS scores at birth and before NNU discharge, but not at one year. One study [38] found that a history of traumatic events, during recent years was not associated with PTS symptoms three to five days after birth, but was associated with PTS among mothers at a later assessment point around one month after birth. Finally, one study [41] found that prior trauma exposure was not associated with a significant increase in PTS scores one to four months after birth. PTS symptoms were higher among women who had a traumatic childbirth compared with those who did not, but no significant association was found in the regression analysis [41].

-

6) Parental postnatal mental health factors (Four factors: postnatal depression, postnatal anxiety, early PTS symptoms, other mental health problems)

The association between postnatal depression and PTS was explored in seven studies [22, 23, 26, 31, 32, 42, 48]. The timing of the assessment varied across the studies: during NNU admission [26, 31, 32, 42], at discharge [22, 23, 26, 32], four months after birth [42] or at one year post discharge among fathers [48]. All studies reported a significant association between postnatal depression and PTS symptoms irrespective of when the measurement was taken.

The association between postnatal anxiety and PTS was explored in five studies [23, 26, 27, 31, 47]. All reported a significant correlation between anxiety scores and PTS scores during NNU admission [26, 31, 47], at three months after birth [27] and at 18 months after birth [23]. In four studies [22, 34, 42, 45], the association between early PTS symptoms and PTS symptoms later in the postnatal period was explored. PTS symptoms around the time of NNU admission was a significant risk factor for an increase in PTS symptoms at one month post discharge [34], at 1–2 months post discharge [22] and 4 months after birth [42]. However, PTS scores during NNU stay were not significantly associated with PTS scores at 6 months [45].

Other mental health symptoms were explored in three studies [24, 26, 42]. The combination of anxiety and depression assessed by the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) was correlated with PTS around birth and before NNU discharge in one study [26]. The combination of high depression and neuroticism scores was a significant risk factor for PTS at six to 48 months after birth in one study [24]. Finally, general psychiatric symptomatology assessed by the Symptom Checklist-90–Revised (SCL-90–R) was significantly correlated with PTS scores in another study [42].

-

7) Parent stress, coping and support factors (11 factors: Parental Stressor Scale total score, stress related to infant’s appearance, stress related to sights and sounds, stress related to parental role alteration, stress related to parent-staff relationships, concurrent stressors, forward-focused coping style, maternal optimism, worry about infant’s death, social support, psychological support).

Parental stress was measured using the Parental Stressor Scale: Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (PSS: NICU) [54] in four studies [31, 41, 42, 48]. The PSS: NICU assesses different domains of stress including sights and sounds, infant appearance and parental role in addition to providing a total parental stress score. Examples of stress related to alteration in the parental role are feeling helpless, being separated from the infant and unable to provide care. Three studies [41, 42, 48] reported PSS total scores; two studies found a significant association with an increase in PTS scores at one to four months after birth [41] or at one year after NNU discharge [48]. However, another study found no association was reported at four months after birth [42]. Two studies [31, 42] reported on parental stress related to infant’s appearance and this was associated with higher PTS scores in one study [31] when PTS was assessed on admission to NNU; another study found no significant association when PTS was measured at 4 months [42]. One study [42] found PTS scores were significantly correlated with the stress related to sights and sounds in the NNU at four months post birth. Stress related to role alteration during NNU admission was evaluated in three studies [22, 31, 42], only one of which found higher stress relating to role alteration correlated with higher PTS scores during NNU admission [31]. One study [42] found that stress relating to relationships with staff during NNU was not significantly correlated with PTS scores.

The number of concurrent stressors was found to be a significant risk factor during NNU admission in one study [34]. Concurrent stressors included social stressors, such as change in relationship status, living arrangements, or job status, and stressors such as loss, personal or family health concerns, experience of a traumatic event or legal problems.

Coping styles and flexibility after a traumatic event were assessed in one study [45] using the perceived ability to cope with trauma scale [55], which has two subscales: forward focus and trauma focus. A forward-focused coping style was not associated with PTS symptoms [45], whereas maternal optimism about the infant’s recovery while in NNU significantly reduced the likelihood of reporting PTS at 6 months [45]. One study explored worry about infant’s death and found it was not associated with PTS during NNU admission [44]. Two studies looked at the association between social support and PTS symptoms [26, 48]. Satisfaction with social support was associated with lower PTS symptoms in one study [26] and maternal social functioning was associated with a reduction in PTS at one year after NNU discharge in another study [48]. Mothers scoring above and below the cut-off point on the modified perinatal PTSD questionnaire were not found to differ in the psychological support they received in a further study [23].

-

8) Other factors (Four factors: geographic separation, active duty, spiritual activities, religious activities)

In a study including military personnel [22], geographic separation (defined as a combat zone deployment of any duration and a separation from family for more than four months at any time, or for more than one month during the most recent pregnancy) and active military service of either parent was not significantly associated with PTS at any time point. In a study of bereaved parents [30], spiritual activity without adopting a specific religion was associated with lower PTS scores among mothers but not fathers, whereas using religious activities as a coping mechanism was not associated with a significant reduction in PTS scores in either parent.

Anxiety

Description of included studies

Table 4 presents the 31 included studies, published in 33 records [27,28,29, 31, 36, 37, 45, 49, 56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74], for anxiety (including 7 studies for both anxiety and PTS).

Twelve studies, published in 13 records, came from USA [27,28,29, 31, 45, 47, 57, 64, 67, 69, 70, 76, 78]. Six studies, published in seven records, were from Europe [36, 37, 49, 56, 58, 59, 72]. Two studies were from Brazil [62, 66] and two from Australia [71, 75], and one was from each of the following countries: New Zealand [68], Canada [65], China [74], Korea [79], Iran [63], Turkey [60], Tunisia [73] and India [77].

Eight studies involved both parents [47, 58, 65, 68, 72, 74, 75], one either parents [76],one [59] included only fathers, and the remaining 21 studies included only mothers. One study only included mothers of babies with congenital anomalies [66], two studies [71, 72] compared multiples to singletons and one study [71] compared bereaved to non-bereaved parents.

GA of the infant was an inclusion criterion in 17 studies, published in 18 records [27, 36, 37, 45, 49, 56, 58, 61,62,63, 65, 67,68,69, 71, 75, 76, 79], and BW was a criterion in eight studies, published in nine records [27,28,29, 31, 61, 65, 67, 68, 71]. One study [72] used both GA and BW to define preterm infants. The studies used various measures of general anxiety symptoms.

Risk of bias assessment

One study [56] was rated at low risk of bias across all domains (See Fig. 3-A summary of risk of bias of anxiety studies and Appendix 3). In the remaining studies, sample selection bias was low in two studies only [65, 68]. Bias due to sample size was low in 14 studies [27, 31, 47, 56, 57, 60, 63, 65, 68, 70, 71, 74, 75, 77]. All except one study [59] used valid measures to assess the factors. Anxiety was assessed via standardised measures in all studies. The bias in the analysis domain was low in eleven studies, published in thirteen records [28, 29, 36, 37, 45, 56, 59, 64, 67, 71, 74, 76, 78]. Reporting bias was low in all except five studies [47, 62, 63, 69, 78] and attrition bias was low in all except in eight studies where it was high [31, 57, 61, 65, 67, 70, 75, 76] and unclear in four [62, 73, 74, 78].

Factors associated with anxiety

Overall, 5,941 parents were involved across the 31 included studies with sample sizes ranging from 29 to 2270 participants. A total of 73 potential risk factors were identified. The risk factors are detailed in Table 5, mapped in Table 6, and summarised here using the same eight categories as for PTS.

-

1) Parent demographic factors (11 factors: age, education, sex, couple’s relationship, family income, employment, ethnicity, residential area, medical insurance, smoking, cumulative psychosocial risk factors).

-

1) Parent demographic factors (Ten factors: age, education, sex, ethnicity, parents’ area deprivation, income, employment status, housing and access to transport, single parent, family social risk).

Parental age was examined as a determinant of anxiety in eight studies [27, 56, 62, 63, 69, 70, 74, 79] and none showed any significant association with developing anxiety at any time point. The association between parental education and anxiety was reported in eight studies [27, 28, 61,62,63, 70, 74, 79]. In one study [61], parents’ educational level correlated negatively with anxiety scores and in another study [74], parents with low education levels had significantly higher anxiety scores. In contrast, in one study [63], mothers with university degrees had higher state anxiety scores after birth compared to mothers with a diploma or lower level of educational attainment. No evidence of association between elevated anxiety scores and parental factors was found in the remaining studies.

The association between sex of parents and anxiety was reported in seven studies [47, 58, 65, 68, 72, 74, 75]. In two studies [47, 68], fathers reported significantly fewer anxiety symptoms than mothers during NNU admission [47] and also at nine months [68]. In all other studies, no significant associations were found. Couple’s relationship was explored in five studies [56, 59, 62, 69, 70]. Being married was associated with lower anxiety scores during NNU admission in one study [70], yet marital status was not associated with anxiety symptoms in the other three studies [56, 62, 69]. A negative description of a couple’s relationship status was associated with greater anxiety scores in fathers two to three weeks after birth in one study [59].

The relationship between family income and anxiety was investigated in six studies [29, 59, 62, 63, 70, 74]. In one study, having a low income status was associated with lower anxiety scores amongst mothers at the time of birth [29]. In contrast, in another study, low family income was associated with elevated paternal anxiety symptom scores after birth [59]. In four studies [62, 63, 70, 74] family income was not significantly correlated with anxiety scores. Employment was explored in five studies [56, 59, 63, 70, 79]. An unemployed father was associated with elevated anxiety scores among fathers at birth in one study [59]. However, in the four other studies, no association was found between parents’ employment status and developing anxiety at birth [63], two to three weeks after birth [79], during NNU admission [70] or at NNU discharge [56]. Three studies [47, 69, 70], considered ethnicity as a factor relevant to anxiety during NNU stay and no significant association was found. Area deprivation was evaluated in relation to anxiety in two studies [74, 76]: parents residing in more economically advantaged areas were found to be 6.5 times more likely to report anxiety two weeks after birth during the NNU stay [76]. Anxiety scores during the first week after birth were lower among mothers living in an urban residential area compared to those living in a rural area [74], and the same study found higher anxiety scores among women without medical insurance compared to those who were insured [74]. One study explored smoking status and found that smoking was not significantly correlated with anxiety [69]. One study [78] looked at a cumulative psychosocial risk factor score, comprising younger maternal age, perceived stress and low socio-economic status),- and found this was significantly associated with greater maternal anxiety scores.

-

2) Pregnancy and birth factors (15 factors: parity, in-vitro fertilisation, multiple pregnancy, number of antenatal visits, preeclampsia, pregnancy complications, cumulative obstetric risks, mode of birth, preterm birth, infant health risk/congenital anomalies, timing of when parents met their newborn, skin to skin, postnatal care education, mother’s length of stay, maternal severe morbidity).

The association between parity and anxiety was explored in nine studies [28, 37, 56, 59, 61,62,63, 69, 79]. Being primiparous, a first time mother, was an independent risk factor associated with anxiety in four studies [28, 37, 59, 79]. Primiparous mothers had significantly higher anxiety scores than multiparous mothers at two to three weeks after birth [79]. Similarly, primiparous mothers were seven times more likely to report anxiety symptoms prior to NNU discharge [28]. Even when the assessment was at six to eighteen months post term, primiparity was still a significant risk factor for state anxiety [37]. However, being primiparous was not associated with state anxiety symptoms at NNU discharge in two studies [56, 69]. In two further studies, multiparous compared to nulliparous mothers exhibited higher state anxiety scores [61, 63]. Furthermore, mothers who had given birth three or more times had higher state and trait anxiety mean scores in one study [63]. No correlation was reported between number of children and anxiety during NNU stay or at discharge [62, 69]. Among fathers [59], a significant association was found between being a first time father and elevated state anxiety scores after birth. Assisted reproductive techniques [59, 79], multiple pregnancy [56, 59, 71, 72, 79], number of antenatal visits [62], and preeclampsia were not significant risk factors for state anxiety at NNU discharge [56]. However, pregnancy complications were significantly correlated with elevated state and trait anxiety scores during NNU stay [62]. A cumulative obstetric risk score comprising preeclampsia, high blood pressure and diabetes was not associated with higher anxiety scores in one study [78]. Mode of birth was considered in five studies [56, 59, 62, 63, 77]. Having a caesarean section after 26 weeks was associated with more state anxiety symptoms compared to spontaneous vaginal birth after 26 weeks, evidence from a large study that adjusted for neonatal birthweight, severe neonatal morbidity, maternal age, employment and parity [56]. No association was found in the remaining four studies [59, 62, 63, 77]. Preterm birth, either induced or spontaneous, was not associated with developing state anxiety at NNU discharge in one good quality study [56]. Two studies looked at the influence of receiving information about health risk or congenital anomaly in the foetus during antenatal scans on anxiety. Among fathers [59], infant health risks detected antenatally were a significant risk factor for anxiety at two–three weeks post birth. However, among mothers, trait anxiety was lower when baby’s diagnosis of congenital anomalies was made antenatally than postnatally [66]. Timing of when parents met their newborn [56], skin to skin contact, [56], receiving postnatal care education [79], mothers’ length of hospitalisation [59] and a composite factor of severe maternal morbidity [56] were not significantly associated with anxiety.

-

3) Infant demographic factors (Six factors: gestational age, birthweight, prematurity, Apgar score, sex, cumulative neonatal risk factor)

Gestation age was considered in seven studies [37, 59, 62, 63, 70, 77, 79]. Mothers to infants born at 33 weeks of gestational age or less experienced higher state anxiety at birth compared to mothers > 34 weeks [63] and at two to three weeks after birth [79]. This was consistent even at a later assessment at six and 18-month post-term age [37]. Among fathers, GA ≤ 28 week vs > 28 was not a significant factor associated with higher state anxiety scores after birth or 2–3 weeks later [59], nor was GA < 37 and ≥ 37 weeks among mothers [77]. Birth weight was reported in eight studies [29, 59, 61,62,63, 70, 73, 77]. Lower BW was significantly correlated with higher anxiety scores in one study [61]. Moreover, each 100 g increase in birthweight was associated with a two point decrease in maternal anxiety in another study [29]. Birthweight ≤ 1500g was not a significant factor among fathers [59]. During NNU, BW was not significantly /associated with anxiety in four studies [62, 70, 73, 77]. No statistically significant difference was found between BW and state anxiety mean scores [63]. Prematurity (an aggregate of infant BW and age) was not correlated with anxiety scores during NNU [70]. Apgar scores [62, 73, 77] and infant’s sex [63, 77, 79] were not significantly associated with anxiety. A cumulative neonatal risk factor, based on BW, GA and Apgar scores, was associated with a significant increase in anxiety scores in one study [78].

-

4) Infant health and care factors (19 factors: clinicians’ perception of infant’s health, mother-infant attachment and bonding, number of NNU visits, feeding, mothers’ participation in baby care, maternal question asking, interaction with health care professionals, mothers understanding of explanations, length of hospitalisation, brain injury, ventilation, number of days on a ventilator, oxygen treatment, antibiotic treatment, severe neonatal morbidity, development, NNU admission reasons,, NNU room, place discharged/transferred to).

Seven studies [27, 45, 49, 61, 67, 70, 76] examined the association between clinicians’ perception of infant’s health and parental anxiety. Clinicians’ perception of infant health was measured using varied scales, the clinical risk index for babies (CRIB) score in [61] and it was a significant risk factor for elevated maternal state anxiety. Similarly, health professional rating of the severity of the infant’s illness assessed via Neurobiologic Risk Score (NBRS) in [27] was significantly correlated with maternal state anxiety at three months after birth. The influence of infant health status on parental anxiety was apparent during NNU stay in three studies [45, 49, 70]. Presence of an infant health problem was a predictor only at first assessment during NNU [45]. Whereas infant perinatal risk status using Perinatal Risk Inventory (PERI) correlated significantly with state anxiety during NNU assessment in [49], and infant illness severity was significantly correlated with anxiety during NNU stay [70]. Infant health determined using the neonatal risk categorisations by [80] was not associated with anxiety one week after birth [67]. Severity of the infant’s condition was not associated with elevated anxiety during NICU stay at two weeks after birth [76]. Maternal-infant attachment/contact and bonding (physical and verbal) while in NNU was negatively correlated with anxiety symptoms in [57], but no significant association was found in Lotterman et.al., nor was the number of NNU visits per week, at assessment six months later [45]. Infant feeding, tube or breast was not significantly associated with more anxiety symptoms in [77]. Mothers’ participation in infant care while in NNU was reported on in two studies [45, 60]. The participation of mothers in many aspects of baby care resulted in reducing state and trait anxiety scores only in [60]. In [45] mothers seeking information and asking technical questions e.g. about the equipment and questions related to baby care, and having a positive relationship with healthcare professionals reduced anxiety scores at NNU but the effect was not significant at six months assessment. Whereas, mothers’ receiving explanations from NNU healthcare providers about treatment procedures and infant’s care and being able to understand were perceived as a calming anxiety factor.

Infant length of stay was reported in six studies [45, 59, 61, 69, 70, 77]. A longer hospital stay was correlated with state and trait anxiety scores in one study [61]. No correlation was found in the remaining studies. Severity of infant brain injury was not correlated with anxiety scores [69]. One study found that mothers’ to infants who required ventilation had significantly higher anxiety scores [79]. However the number of days on a ventilator was not correlated significantly with anxiety in another [69]. Both oxygen treatment and antibiotic treatment were associated with higher anxiety scores in [79], but severe neonatal morbidity was not associated with higher state or trait anxiety scores at NNU discharge in another study [56]. Infant development score using a Generalised Developmental Quotient (GQ) [81] at one year was not correlated with state or trait anxiety in one study [49].

The reasons for NNU admission, whether it was surgical, medical or for observation, was not associated with more anxiety symptoms at one month post-birth [77]. Type of neonatal room, whether single or multiple, was not associated with more trait anxiety symptoms [56]. Place discharged to, home or transfer to another hospital, was not a significant risk factor for increased state anxiety symptoms [56], whereas being in hospital rather than discharged home was significantly associated with higher anxiety scores [79].

-

5) Parental history of mental health problems and trauma factors (Six factors: history of mental condition, history of depression, history of mental health condition any family member, stressful life events, panic and trauma, anxious arousal symptoms).

Three studies [45, 59, 69] reported on the association between parental history of mental health conditions, eg. depression, anxiety or bipolar disorders and developing anxiety, none reported any significant association. Two studies [64, 70] looked at the impact of a previous history of depression and both reported a significant correlation with anxiety scores during NNU. A history of mental health problems of any family member and anxiety scores was reported on in [59] and no significant association with anxiety was found. Stressful life events were not correlated with anxiety scores at NNU discharge in [69], however, panic and trauma symptoms were significantly correlated with anxiety [70]. Similarly anxious arousal, a composite variable for panic, was significantly correlated with anxiety [70].

-

6) Parental postnatal mental health factors (Three factors: postpartum depression, posttraumatic stress symptoms (PTS), persistent anxiety)

Postpartum depression was reported in eight studies [27, 28, 31, 47, 62, 70, 73, 79] all of which found a significant association with anxiety. Postpartum depressive symptoms after birth significantly increased the odds of developing anxiety prior to discharge [28]. Also, depressive symptoms correlated significantly with state anxiety scores during NNU [31, 62], prior to NNU discharge, at two to three weeks after birth [79], and at three months after birth [27]. Anxiety symptoms and postpartum depression were significantly correlated during NNU stay [70, 73]. Two studies looked at PTS and found a significant correlation between postpartum depression and state anxiety/anxiety [27, 47]. Early anxiety symptoms during NNU were not a predictor for anxiety six months later [45].

-

7) Parent stress, coping and support factors (Ten factors: Infant’s appearance of stress, stressful sights and sounds, parental role alterations, staff behaviour and communication, PSS scores, coping style, optimism, parents’ resilience, guilt feeling, social support).

Parental stress was measured by Parental Stressor Scale: NICU (PSS: NICU) [54] in four studies [27, 31, 59, 69], one further study [59] reported on PSS four subscales. Infant’s appearance and behaviour stress subscale was reported on in two studies [31, 59] and it was found to be a significant stressor for state anxiety in both: In [59] after birth and at 2–3 weeks afterwards, and in [31] during NNU assessment. Stressful sights and sounds in NNU were associated with state anxiety only at first assessment after birth in [59]. Parental role alterations stress (e.g. not being able to feed the infant) in the NNU was a significant factor of more state anxiety symptoms after birth and two to three weeks afterwards in [59] and during NNU [31]. In contrast, no correlation was found in [69]. Stress related to staff-behaviour and communication was not correlated with fathers’ anxiety scores [59]. Total PSS score measuring overall parental stress was directly correlated with state anxiety at three months after birth in [27]. Furthermore, elevated PSS scores was associated with higher state anxiety scores in [59].

The relationship between maternal coping strategies and anxiety level was examined in one study [45]. Forward coping style was associated with lower anxiety scores during NNU [45]. There was no significant association between maternal optimism about the infant’s recovery and anxiety scores at six months [45]. Parents’ resilience was not a risk factor for anxiety during NICU stay at two weeks post birth [76]. Mothers’ feeling of guilt scores, based on scores for fault, responsibility, punishment, and feelings of helplessness, was significantly correlated with state anxiety scores at two to three weeks after birth [79].

Fathers’ perception of social support and satisfaction with social support were significantly associated with reduced state anxiety scores soon after birth, but not at a later assessment two to three weeks afterwards [59]. Similarly, maternal satisfaction with social support was not correlated with anxiety scores at NNU discharge [69]. How parents perceived social support was not an independent anxiety risk factor during the first two weeks of NNU stay [76].

-

8) Other factors (Three factors: bereavement, grief and suffering, maternal physical health)

Two studies [58, 71] included parents who experienced bereavement. All parents were bereaved in [58] and in [71] bereaved parents were compared to non-bereaved parents. There was a significant correlation between bereavement and anxiety scores among mothers but not fathers [58]. Bereaved families showed more anxiety symptoms than non-bereaved families even at seven years corrected age [71], yet no difference was found regarding clinically diagnosed anxiety between the two groups.

The grief/suffering scores at two to six years after the loss of the baby were not significantly correlated with anxiety [58]. Maternal physical health such as fatigue and shoulder pain were significantly correlated with state anxiety at two to three weeks after birth in [79].

Discussion

This review is the first to systematically synthesise factors associated with PTS and anxiety symptoms among parents of infants admitted to NNU. There was significant methodological variability across the 49 included studies, involving 8,447 parents. This was due to differences in study design, inclusion criteria, timing of assessment, measuring tools and cut-off values used. There was also vast variations in defining and reporting on similar factors across the included studies. Therefore, the findings were synthesised narratively.

Although the majority of the identified factors were based on one or two small studies, several factors emerged from multiple studies that could allow healthcare professionals to determine which of these parents require more attention, early screening, referral and intervention before developing PTS and anxiety. Healthcare professionals should target those parents with previous diagnoses of mental health problems before pregnancy and parents who develop any mental health conditions during antenatal and postnatal periods. As seen in the general perinatal population, anxiety, depression and PTS are all highly comorbid conditions among parents of NNU infants [82,83,84,85].

Factors specific to this population associated with PTS or anxiety included preterm birth (≤ 33 weeks), having an extremely low birthweight (< 1000 g) infant and stressors in the NNU environment, in particular the infants’ appearance and behaviour. Unexpectedly, a number of factors specific to this group of parents showed no association with PTS or anxiety, such as reasons for NNU admission, severe neonatal morbidity, ventilation duration and number of NNU visits, although these results should be interpreted with caution because each of the findings were based on a single study.

A factor consistently found to be associated with PTS was the parents’ own perception of the severity of the infant’s illness. Also when staff did not convey information clearly, it caused emotional stress to the parents and left them feeling powerless and excluded [86]. In addition to good communication, active parent involvement in baby’s care while in NNU is a protective factor found in this review to reduce anxiety, as parents felt more comfortable and prepared to care for their baby after discharge [87] thus enhancing the long term positive impacts for the whole family [88]. Other studies have found fewer medical interventions to the infant and better infant development was seen after parents making physical contact with their infant while in NNU [89]. Also participation of parents in baby’s care during NICU, as part of a family centred intervention, was associated with a positive impact on infant’s clinical outcomes and a shorter NNU stay as reported in [90]. Overall, our findings highlight that protective factors around the care provided include communicating well with parents, asking about their perception of how ill their infant is and involving them in providing care to their infants.

Another protective factor for both PTS and anxiety was positive coping mechanisms used by parents after unexpected NNU admission. Encouraging parents to utilise positive coping or adapt their coping styles, such as by taking ‘time out’ or ‘debriefing’ when things go wrong, could be effective in improving their state of mental health and well-being [86, 87]. Parents’ degree of greater perceived social support and having a functioning social support setup also emerged as a protective factor for PTS therefore having wider targeted family psychological support and peer to peer support networks could have a positive impact on parents’ mental health [86]. Early engagement of peer-to-peer support during NNU stay and beyond discharge has also been found to be effective in improving stress, anxiety and depression symptoms [91, 92].

Implications for practice and research

As with the general perinatal population a history of mental health problems and having co-morbid mental health conditions are factors associated with both anxiety and PTS in parents of babies admitted to NNU. Therefore, early screening of all parents for mental health problems is the best way to provide much needed information on which parents may need psychological support. As with the general perinatal population, increased awareness amongst healthcare professionals of the influence of history of mental health and co-morbid mental health problems is important in understanding the mental health needs of parents. Parent’s perception of infant illness is a distinctive factor for this group. Therefore clear communication, enquiring into the parents’ perception of their infant’s illness, and early participation of parents in the care of their babies may also ease symptoms of anxiety and PTS.

Bereaved parents are an important subgroup of NNU parents on which there were little data, therefore exploring the needs of these parents while in NNU and their long term comprehensive psychosocial support needs after the loss of the infant is crucial. Another major gap in the literature is the mental health of the fathers and non-traditional family models such as a single parent and same sex families of infants admitted to NNU. Future research should ensure fathers and parents of non-traditional families are included to better understand partner risk factors for PTS and anxiety, and how maternal and partner risk factors interact. Additional research targeting younger parents and those from different ethnic backgrounds is also needed, as are studies in low and middle income settings.

Improving the methodological rigor and standardising approaches to measurement of common mental health problems would add significantly to the current literature. For example, consensus between researchers on the tools and cut-off points for this population is needed. Expanding the scope of routine data collection to include parental risk factors, and linking to existing routine maternity/ primary care data sets would provide population level data to explore parent mental health risk factors more robustly. As many psychosocial risk factors are not routinely collected, a large, more population-based cohort study that additionally includes parents whose babies did not require NNU admission would help better predict the most at risk groups.

Strengths and limitations

The review is a rigorous, comprehensive synthesis of an important research area. We adopted broad, inclusive eligibility criteria and followed a transparent research approach in line with the PRISMA 2020 recommendation. Robust risk of bias assessment and reporting on multivariable analysis, when available, helped reduce the risk of bias in reporting and interpretation of findings. A large number of studies were included in the review, however, despite comprehensive searching and contacting authors, the full texts from 11 studies could not be retrieved. It was not possible to separate out ASD and PTSD in the review as studies collected data over different time periods and often did not differentiate the one month cut-off for ASD. Meta-analysis of data was not feasible as many of the risk factors were examined in one study only, and where more than one study described a risk factor there was considerable methodological heterogeneity in study design, analysis, confounder factors and reporting, combined with clinical heterogeneity, different measures/cut-off points and variation in assessment time. While the data were too heterogeneous to meta-analyse, visually mapping the evidence provides an informative summary of the magnitude of data available for each risk factor.

Conclusion

There is insufficient evidence to support a targeted approach to identifying parents at risk of developing anxiety and PTS when their baby is admitted to NNU. As with the general perinatal population, previous mental health and current co-morbid depression are risk factors for anxiety and PTS. Taking time to communicate well with parents and understand their perceptions of infants’ health may protect parents from experiencing anxiety and PTS symptoms. More research is needed to understand the impact of the NNU environment on parents’ mental health and also the association of low birth weight and a shorter gestational age with anxiety and PTS symptoms. There is some evidence, albeit limited, to suggest that engaging parents early in baby’s care and providing adequate social support may benefit the parents’ mental health. In the absence of evidence to support a targeted approach, routine screening for PTS and anxiety should be offered to all parents, even though, the optimal screening tool and the best administration time are not yet well established for this population.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

References

Hawes K, McGowan E, O’Donnell M, Tucker R, Vohr B. Social Emotional Factors Increase Risk of Postpartum Depression in Mothers of Preterm Infants. J Pediatr. 2016;179:61–7.

Williams KG, Patel KT, Stausmire JM, Bridges C, Mathis MW, Barkin JL. The Neonatal Intensive Care Unit: Environmental Stressors and Supports. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(1):60.

Roque ATF, Lasiuk GC, Radünz V, Hegadoren K. Scoping Review of the Mental Health of Parents of Infants in the NICU. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2017;46(4):576–87.

Vigod S, Villegas L, Dennis C-L, Ross L. Prevalence and risk factors for postpartum depression among women with preterm and low-birth-weight infants: a systematic review. BJOG: An Int J Obstet Gynaecol. 2010;117(5):540–50.

Malouf R, Harrison S, Burton HAL, Gale C, Stein A, Franck LS, et al. Prevalence of anxiety and post-traumatic stress (PTS) among the parents of babies admitted to neonatal units: A systematic review and meta-analysis. EClinicalMedicine. 2022;43: 101233.

Lakshmanan A, Agni M, Lieu T, Fleegler E, Kipke M, Friedlich PS, et al. The impact of preterm birth <37 weeks on parents and families: a cross-sectional study in the 2 years after discharge from the neonatal intensive care unit. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2017;15(1):38-.

Qin X, Liu C, Zhu W, Chen Y, Wang Y. Preventing Postpartum Depression in the Early Postpartum Period Using an App-Based Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Program: A Pilot Randomized Controlled Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(24):16824.

NICE, editor. NICEimpact maternity and neonatal care-Maternity and mental health. https://www.nice.org.uk/about/what-we-do/into-practice/measuring-the-use-of-nice-guidance/impact-of-our-guidance/niceimpact-maternity/ch2-maternity-and-mental-health2023.

Biaggi A, Conroy S, Pawlby S, Pariante CM. Identifying the women at risk of antenatal anxiety and depression: A systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2016;191:62–77.

Soto-Balbuena C, Rodríguez MF, Escudero Gomis AI, Ferrer Barriendos FJ, Le HN, Pmb-Huca G. Incidence, prevalence and risk factors related to anxiety symptoms during pregnancy. Psicothema. 2018;30(3):257–63.

Giacchino T, Karkia R, Zhang W, Beta J, Ahmed H, Akolekar R. Kielland’s rotational forceps delivery: A comparison of maternal and neonatal outcomes with rotational ventouse or second stage caesarean section deliveries. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2020;254:175–80.

Fischbein RL, Nicholas L, Kingsbury DM, Falletta LM, Baughman KR, VanGeest J. State anxiety in pregnancies affected by obstetric complications: A systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2019;257:214–40.

Furuta M, Sandall J, Cooper D, Bick D. Predictors of birth-related post-traumatic stress symptoms: secondary analysis of a cohort study. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2016;19(6):987–99.

Martinez-Vázquez S, Rodríguez-Almagro J, Hernández-Martínez A, Martínez-Galiano JM. Factors Associated with Postpartum Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) Following Obstetric Violence: A Cross-Sectional Study. Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2021;11(5):338.

Chan SJ, Ein-Dor T, Mayopoulos PA, Mesa MM, Sunda RM, McCarthy BF, et al. Risk factors for developing posttraumatic stress disorder following childbirth. Psychiatry Res. 2020;290: 113090.

NHS & DH. NHS & DH. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH. 2009. Toolkit for High Quality Neonatal Services. http://www.londonneonatalnetwork.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Toolkit-2009.pdf. Accessed June 2022 2009.

Stark AR. Levels of neonatal care. Pediatrics. 2004;114(5):1341–7.

American Psychiatric Association. Anxiety disorders. In Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th. ed2013.

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372: n71.

Covidence systematic review software. Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia. Available at www.covidence.org.

Wells G, Shea B OCD, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, Tugwell P The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. 2013, http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp,. 2013.

Anchan J, Jones S, Aden J, Ditch S, Fagiana A, Blauvelt D, et al. A different kind of battle: the effects of NICU admission on military parent mental health. J Perinatol. 2021;41(8):2038–47.

Brunson E, Thierry A, Ligier F, Vulliez-Coady L, Novo A, Rolland AC, et al. Prevalences and predictive factors of maternal trauma through 18 months after premature birth: A longitudinal, observational and descriptive study. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(2):e0246758.

Chang HP, Chen JY, Huang YH, Yeh CJ, Huang JY, Su PH, et al. Factors Associated with Post-Traumatic Symptoms in Mothers of Preterm Infants. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2016;30(1):96–101.

Clark OE, Fortney CA, Dunnells ZDO, Gerhardt CA, Baughcum AE. Parent Perceptions of Infant Symptoms and Suffering and Associations With Distress Among Bereaved Parents in the NICU. J Pain and Symptom Manage. 2021;62(3):e20–7.

Eutrope J, Thierry A, Lempp F, Aupetit L, Saad S, Dodane C, et al. Emotional reactions of mothers facing premature births: Study of 100 mother-infant dyads 32 gestational weeks. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(8):e104093.

Garfield L, Holditch-Davis D, Carter CS, McFarlin BL, Schwertz D, Seng JS, et al. Risk factors for postpartum depressive symptoms in low-income women with very low-birth-weight infants. Adv Neonatal Care. 2015;15(1):E3–8.

Greene MM, Rossman B, Patra K, Kratovil AL, Janes JE, Meier PP. Depression, anxiety, and perinatal-specific posttraumatic distress in mothers of very low birth weight infants in the neonatal intensive care unit. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2015;36(5):362–70.

Greene MM, Schoeny M, Rossman B, Patra K, Meier PP, Patel AL. Infant, Maternal, and Neighborhood Predictors of Maternal Psychological Distress at Birth and Over Very Low Birth Weight Infants’ First Year of Life. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2019;40(8):613–21.

Hawthorne DM, Youngblut JM, Brooten D. Parent Spirituality, Grief, and Mental Health at 1 and 3 Months After Their Infant’s/Child’s Death in an Intensive Care Unit. J Pediatr Nurs. 2016;31(1):73–80.

Holditch-Davis D, Miles MS, Weaver MA, Black B, Beeber L, Thoyre S, et al. Patterns of distress in African-American mothers of preterm infants. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2009;30(3):193–205.

Jubinville J, Newburn-Cook C, Hegadoren K, Lacaze-Masmonteil T. Symptoms of acute stress disorder in mothers of premature infants. Adv Neonatal Care. 2012;12(4):246–53.

Kim WJ, Lee E, Kim KR, Namkoong K, Park ES, Rha DW. Progress of PTSD symptoms following birth: A prospective study in mothers of high-risk infants. J Perinatol. 2015;35(8):575–9.

Lefkowitz DS, Baxt C, Evans JR. Prevalence and correlates of posttraumatic stress and postpartum depression in parents of infants in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU). J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2010;17(3):230–7.

Malin KJ, Johnson TS, McAndrew S, Westerdahl J, Leuthner J, Lagatta J. Infant illness severity and perinatal post-traumatic stress disorder after discharge from the neonatal intensive care unit. Early Hum Dev. 2020;140:104930.

Misund AR, Nerdrum P, Braten S, Pripp AH, Diseth TH. Long-term risk of mental health problems in women experiencing preterm birth: A longitudinal study of 29 mothers. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2013;12(1):33.

Misund AR, Nerdrum P, Diseth TH. Mental health in women experiencing preterm birth. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14(1):263.

Naeem AT, Shariat M, Zarkesh MR, Abedinia N, Bakhsh ST, Nayeri F. The incidence and risk factors associated with posttraumatic stress disorders among parents of NICU hospitalized preterm neonates. Iranian J Neonatol. 2019;10(4):76–82.

Pace CC, Anderson PJ, Lee KJ, Spittle AJ, Treyvaud K. Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms in Mothers and Fathers of Very Preterm Infants Over the First 2 Years. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2020;41(8):612–8.

Rodriguez DC, Ceriani-Cernadas JM, Abarca P, Edwards E, Barrueco L, Lesta P, et al. Chronic post-traumatic stress in mothers of very low birth weight preterm infants born before 32 weeks of gestation. Arch Argent Pediatr. 2020;118(5):306–12.

Sharp M, Huber N, Ward LG, Dolbier C. NICU-Specific Stress following Traumatic Childbirth and Its Relationship with Posttraumatic Stress. J Perinat Neonat Nurs. 2021;35(1):57–67.

Shaw RJ, Bernard RS, Deblois T, Ikuta LM, Ginzburg K, Koopman C. The relationship between acute stress disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder in the neonatal intensive care unit. Psychosomatics. 2009;50(2):131–7.

Vinall J, Noel M, Disher T, Caddell K, Campbell-Yeo M. Memories of infant pain in the neonatal intensive care unit influence posttraumatic stress symptoms in mothers of infants born preterm. Clin J Pain. 2018;34(10):936–43.

Williams AB, Hendricks-Munoz KD, Parlier-Ahmad AB, Griffin S, Wallace R, Perrin PB, et al. Posttraumatic stress in NICU mothers: modeling the roles of childhood trauma and infant health. J Perinat. 2021;41(8):2009–18.

Lotterman JH. Factors impacting psychological and health outcomes in mothers and infants following NICU hospitalization of the infant. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering. 2018;79(1-B E). https://doi.org/10.7916/D83R1591.

Malin KJ, Johnson TS, Brown RL, Leuthner J, Malnory M, White-Traut R, et al. Uncertainty and perinatal post-traumatic stress disorder in the neonatal intensive care unit. Res Nurs Health. 2022;45(6):717–32.

Moreyra A, Dowtin LL, Ocampo M, Perez E, Borkovi TC, Wharton E, et al. Implementing a standardized screening protocol for parental depression, anxiety, and PTSD symptoms in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. Early Hum Dev. 2021;154: 105279.

Salomè S, Mansi G, Lambiase CV, Barone M, Piro V, Pesce M, et al. Impact of psychological distress and psychophysical wellbeing on posttraumatic symptoms in parents of preterm infants after NICU discharge. Ital J Pediatr. 2022;48(1):13.

Pisoni C, Spairani S, Fauci F, Ariaudo G, Tzialla C, Tinelli C, et al. Effect of maternal psychopathology on neurodevelopmental outcome and quality of the dyadic relationship in preterm infants: an explorative study. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2020;33(1):103–12.

Kim DW, Kim HG, Kim JH, Park K, Kim HK, Jang JS, et al. Randomized phase III trial of irinotecan plus cisplatin versus etoposide plus cisplatin in chemotherapy-naive Korean patients with extensive-disease small cell lung cancer. Cancer Res Treat. 2019;51(1):119–27.

Scheiner AP, Sexton ME. Prediction of developmental outcome using a perinatal risk inventory. Pediatrics. 1991;88(6):1135–43.

Brazy JE, Goldstein RF, Oehler JM, Gustafson KE, Thompson RJ Jr. Nursery neurobiologic risk score: levels of risk and relationships with nonmedical factors. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 1993;14(6):375–80.

Crittenden PM. CARE-Index. Coding Manual. 1979–2004.

Miles MS, Funk SG, Carlson J. Parental Stressor Scale: neonatal intensive care unit. Nurs Res. 1993;42(3):148–52.

Bonanno GA, Pat-Horenczyk R, Noll J. Coping flexibility and trauma: The Perceived Ability to Cope With Trauma (PACT) scale. Psychol Trauma Theory Res Pract Policy. 2011;3(2):117–29.

Blanc J, Rességuier N, Lorthe E, Goffinet F, Sentilhes L, Auquier P, et al. Association between extremely preterm caesarean delivery and maternal depressive and anxious symptoms: a national population-based cohort study. Int J Obstet Gynaecol. 2021;128(3):594–602.

Bonacquisti A, Geller PA, Patterson CA. Maternal depression, anxiety, stress, and maternal-infant attachment in the neonatal intensive care unit. J Reprod Infant Psychol. 2020;38(3):297–310.

Buchi S, Morgeli H, Schnyder U, Jenewein J, Hepp U, Jina E, et al. Grief and post-traumatic growth in parents 2–6 years after the death of their extremely premature baby. Psychother Psychosom. 2007;76(2):106–14.

Cajiao-Nieto J, Torres-Gimenez A, Merelles-Tormo A, Botet-Mussons F. Paternal symptoms of anxiety and depression in the first month after childbirth: A comparison between fathers of full term and preterm infants. J Affect Disord. 2021;282:517–26.

Cakmak E, Karacam Z. The correlation between mothers’ participation in infant care in the NICU and their anxiety and problem-solving skill levels in caregiving. Journal of Maternal-Fetal and Neonatal Medicine. 2018;31(1):21–31.

Carvalho AE, Martinez FE, Linhares MB. Maternal anxiety and depression and development of prematurely born infants in the first year of life. Spanish Journal of Psychology. 2008;11(2):600–8.

Dantas MMrC, de Araújo PCB, Santos LcMdO, Pires NA, Maia ElMC. Symptoms of anxiety and depression in mothers of hospitalized premature infants. J Nurs UFPE /Revista de Enfermagem UFPE. 2012;6(2):279–87.

Damanabad ZH, Valizadeh L, Arani MM, Hosseini M, Jafarabadi MA, Mansourian M, et al. Evaluation of Maternal Anxiety in Mothers of Infants Admitted to the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. Int J Pediatr-Mashhad. 2019;7(10):10215–24.

Das A, Gordon-Ocejo G, Kumar M, Kumar N, Needlman R. Association of the previous history of maternal depression with post-partum depression, anxiety, and stress in the neonatal intensive care unit. J Matern-Fetal Neonat Med. 2021;34(11):1741–6.

Feeley N, Gottlieb L, Zelkowitz P. Mothers and fathers of very low-birthweight infants: Similarities and differences in the first year after birth. J Obstet, Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2007;36(6):558–67.

Fontoura FC, Cardoso M, Rodrigues SE, de Almeida PC, Carvalho LB. Anxiety of mothers of newborns with congenital malformations in the pre- and postnatal periods. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem. 2018;26:e3080.

Gennaro S. Postpartal anxiety and depression in mothers of term and preterm infants. Nurs Res. 1988;37(2):82–5.

Mulder RT, Carter JD, Frampton CMA, Darlow BA. Good two-year outcome for parents whose infants were admitted to a neonatal intensive care unit. [References] Psychosomatics. 2014;55(6):613–20.

Rogers CE, Kidokoro H, Wallendorf M, Inder TE. Identifying mothers of very preterm infants at-risk for postpartum depression and anxiety before discharge. J Perinatol. 2013;33(3):171–6.

Segre LS, McCabe JE, Chuffo-Siewert R, O’Hara MW. Depression and anxiety symptoms in mothers of newborns hospitalized on the neonatal intensive care unit. Nurs Res. 2014;63(5):320–32.

Treyvaud K, Aldana AC, Scratch SE, Ure AM, Pace CC, Doyle LW, et al. The influence of multiple birth and bereavement on maternal and family outcomes 2 and 7years after very preterm birth. Early Human Dev. 2016;100:1–5.

Zanardo V, Freato F, Cereda C. Level of anxiety in parents of high-risk premature twins. Acta Genet Med Gemellol. 1998;47(1):13–8.

Khemakhem R, Bourgou S, Selmi I, Azzabi O, Belhadj A, Siala N. Preterm birth, mother psychological state and mother- infant bonding. Tunis Med. 2020;98(12):992–7.

Kong L-P, Cui Y, Qiu Y-F, Han S-P, Yu Z-B, Guo X-R. Anxiety and depression in parents of sick neonates: A hospital-based study. [References]J Clin Nurs. 2013;22(7–8):1163–72.

Dickinson C, Vangaveti V, Browne A. Psychological impact of neonatal intensive care unit admissions on parents: A regional perspective. Aust J Rural Health. 2022;30(3):373–84.

Okito O, Yui Y, Wallace L, Knapp K, Streisand R, Tully C, et al. Parental resilience and psychological distress in the neonatal intensive care unit. J Perinatol. 2022;42(11):1504–11.

Shivhare AS R., Choudhary P. P., Alok R. Stressful Experiences of Mothers of Neonates or Premature Infants in a Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. Int J Pharm Clin Res. 2022;14(7):117–26.