- Research

- Open access

- Published:

Advancing health equity for Indigenous peoples in Canada: development of a patient complexity assessment framework

BMC Primary Care volume 25, Article number: 144 (2024)

Abstract

Background

Indigenous patients often present with complex health needs in clinical settings due to factors rooted in a legacy of colonization. Healthcare systems and providers are not equipped to identify the underlying causes nor enact solutions for this complexity. This study aimed to develop an Indigenous-centered patient complexity assessment framework for urban Indigenous patients in Canada.

Methods

A multi-phased approach was used which was initiated with a review of literature surrounding complexity, followed by interviews with Indigenous patients to embed their lived experiences of complexity, and concluded with a modified e-Delphi consensus building process with a panel of 14 healthcare experts within the field of Indigenous health to identify the domains and concepts contributing to health complexity for inclusion in an Indigenous-centered patient complexity assessment framework. This study details the final phase of the research.

Results

A total of 27 concepts spanning 9 domains, including those from biological, social, health literacy, psychological, functioning, healthcare access, adverse life experiences, resilience and culture, and healthcare violence domains were included in the final version of the Indigenous-centered patient complexity assessment framework.

Conclusions

The proposed framework outlines critical components that indicate the presence of health complexity among Indigenous patients. The framework serves as a source of reference for healthcare providers to inform their delivery of care with Indigenous patients. This framework will advance scholarship in patient complexity assessment tools through the addition of domains not commonly seen, as well as extending the application of these tools to potentially mitigate racism experienced by underserved populations such as Indigenous peoples.

Introduction

Indigenous peoples in Canada include First Nations, Métis, and Inuit peoples, who are the descendants of original inhabitants of the territories claimed in the British North American Act; these peoples now represent 5% of the total country’s population [1, 2], exceeding the growth rate of the non-Indigenous population [3]. Preceding European settlers, Indigenous peoples had established sophisticated self-governing nations reflecting their distinct cultures and diverse languages [4, 5]. Prior to European contact, in general, Indigenous peoples had good health buffered by active ways of life and balanced, nutritional diets that promoted longevity [6,7,8]. Colonization was an ethnic and cultural genocide with devastating impacts that have persisted until the present-day [9,10,11]. Calculated practices and policies such as land displacement, forced removal of children from their communities, and the spread of novel and deadly diseases by European settlers extinguished many Indigenous communities and burdened those who survived [12,13,14,15,16,17], undermining their Ways of Being, Doing, and Knowing [18, 19]. Ample research has linked the longstanding impacts of colonialism directly to the burden of disease and poverty that is experienced by Indigenous peoples today [20,21,22]. The current study seeks to extend beyond profiling such impacts to identify possibilities for orienting healthcare providers (HCPs) to better respond to the resulting health inequities.

Though Canada has now embarked on a journey of reconciliation with Indigenous peoples to acknowledge the past and its present-day impacts [23, 24], the consequences of forced assimilation cannot be entirely undone and are most evident within the vast health inequities that exist between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples [25,26,27]. In addition to significantly lower life expectancies than their non-Indigenous counterparts [28, 29], Indigenous peoples are disproportionately burdened by diabetes [30, 31], problem substance use [32, 33], perinatal health inequities [34], arthritis [35], and mental health concerns [36, 37] among many other health problems [20, 38]. While persistent disparities attributed to historical consequences have shaped the health of many Indigenous peoples [39, 40], current healthcare systems continue to amplify these inequities through entrenched and systemic racism, played out in discrimination, unequal treatment, and outright violence towards Indigenous peoples [41, 42]. Racism has been described as an “epidemic” within Canadian healthcare systems and a significant contributor to poorer health outcomes by means of stress and harm arising from discriminatory interactions [43,44,45]. Racial discrimination is also evident in the foundation of healthcare systems, which operate on a Western biomedical epistemology of health that tends to situate disease within the physical bodies of individual patients [46,47,48,49], dismissing repercussions of a colonial legacy impacting genetically, culturally, and geographically diverse populations with a shared experience of oppression from colonization [50, 51].

With healthcare systems denying Indigenous peoples’ needs and priorities [52,53,54], Indigenous patients’ become viewed increasing through the lens of having “complex health needs” [55, 56]. Factors that contribute to this “complexity” are rooted in a legacy of colonization yet often go unnoticed in clinical settings, creating discordance between Indigenous patients and their HCP, as well as discordance between Indigenous patients and broader health systems [57, 58]. Although there is no universal and agreed-upon definition of patient complexity and/or health complexity (terms often used interchangeably within the literature) core indicators include higher healthcare resource utilization, increased need of support, higher risk of adverse health outcomes, and lower satisfaction with care [59, 60]. It is however agreed that patient complexity is not simply co- or multi-morbidity which is marked by the presence of two or more diseases [61]. While co- and/or multi-morbidity may cause a patient to present as “more” complex than patients with a single disease, as in defying easy resolution to their conditions, it is not the only factor that causes a patient to present as complex [61].

Patient complexity is deemed to arise from a patient’s socioeconomic status, environmental and mental health factors, along with the coordination of care and medical decision making which can all complicate a patient’s diagnosis and/or course of treatment causing complexity to arise [62, 63]. Identified domains of patient complexity include:

“demographics (e.g., age, sex, race, and culture), patient personal characteristics or behavior (e.g., communication, burden of disease, coping strategies, and resilience), socio-economic factors, medical, and mental health (e.g., severity of illness, psychiatric disorders, addiction, cognitive impairment), patient risk of mortality, and healthcare system (e.g., care coordination and healthcare utilization), medical decision-making, and environment (e.g., pollution and neighborhood).” [62]

While the conceptualization of patient complexity may be novel to the Western biomedical understandings of health, it serves to reaffirm that broader social factors external to individuals and their physical bodies remain largely unexplored in clinical practice [64].

Given that health inequities across large populations, such as Indigenous peoples, can translate into a higher burden on healthcare systems by way of taxing limited available resources [65], identifying and acting on patient complexity to improve care may feasibly promote better resource allocation to meet patient needs. Patients with complexity often require interventions that are beyond the scope of typical biomedical care and the training of most HCPs [63], which is compounded by healthcare systems being ill-equipped to provide HCPs the appropriate resources necessary to care for patients [64].

Identifying patient complexity is increasingly important, therefore a variety of instruments exist to identify and address patient complexity within different healthcare settings, outpatient or in-patient (including hospitals, treatment centers, and long-term care facilities). Patient complexity assessment tools (PCATs) have emerged as means to aid HCPs in collecting vital information to more effectively deliver care [66,67,68,69]. PCATs may provide a comprehensive assessment that considers all aspects of a patient’s needs, and they are inclusive of the patient's experience of their own health [66,67,68, 70]. PCATs have been noted to enhance patient engagement, more accurately identify the source of complexity challenging care plans, and allow HCPs to engage in appropriate courses of action (e.g. referrals), to improve the health of a patient with complexity [66,67,68, 70].

PCATs follow two common formats, these being: i) a face-to-face interview between a patient and provider where the provider determines the responses within the PCAT, or ii) for patients to complete in written or digital form on their own in a self-assessment method [65]. PCATs may be specific to in-patient or outpatient populations, and in the case of some populations such as the elderly, PCATs may be applicable to those outside of healthcare settings too [65, 71, 72]. Though PCATs present great utility in identifying patient needs, sources of their complexity, and their resources, limited longitudinal data supports their utility beyond these. Few studies have investigated associations between a patient’s complexity and their subsequent healthcarerelated costs [73,74,75] and impacts on HCPs [76].

Despite utility for general patient populations, existing PCATs remain inadequate to effectively address the needs of Indigenous patients, as factors most relevant to Indigenous populations often remain under-explored [55]. HCPs rarely understand the full scope of the contributors of poor health that arise from colonial traumas and the impacts of structural inequities that continue to influence the health of Indigenous peoples [50, 77]. Recognizing this gap, the current research aims to identify components that are critical to include in a PCAT developed for use with Indigenous patients. A program of research was undertaken to a) determine the extent to which existing PCATs contain domains for inquiry relevant to the care of Indigenous patients [55], b) explore the components of health complexity among Indigenous patients and the circumstances that allow it to persist [56], and c) identify the most effective constructs that characterize these complexities. The present study aims to engage a diverse panel of healthcare experts to reach consensus on which domains, concepts, and items are critical to effectively assess health complexity among Indigenous patients. Concepts are defined as constructs that represent a logical category while items are those which measure something. This work describes the development of an Indigenous-centered patient complexity assessment framework. The framework will then ultimately be used to derive an appropriate PCAT.

Methods

Positionality

The first author, AS, is a settler woman who completed this study as part of her PhD research. The second author, RH, is a settler woman and medical anthropologist who works as an assistant professor and primary care models of care scientist. The third author, AM, is a man of Ukrainian, Irish and Apache descent, and works as an assistant professor of Indigenous psychology. The fourth author, LC, is a Piikani First Nation’s man who works as an associate professor, family physician-scholar and assistant dean, and was a co-supervisor for the first author. The last author, CB, is a Métis woman and a mid-career clinician-scientist in rheumatology and health services research who was the primary supervisor for the first author. As a collective, the team was composed of individuals from both Indigenous and non-Indigenous backgrounds. The authors purposefully approached the research to bring forth unique perspectives with a shared commitment to doing research in a ‘good way’ respecting Indigenous research methodologies and remaining conscious of biases and assumptions.

Development of core framework structure and candidate item pool

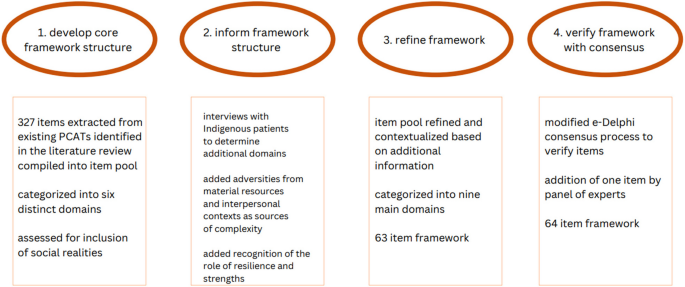

The framework was developed over the course of four main phases. In the first phase, the core framework structure was identified primarily through review of existing PCATs. In the second phase, the framework was informed by the lived experience of Indigenous patients to embed additional domains relevant to this patient population. In phase three, the framework was refined and categorized logically. Finally, in phase four, the framework was verified with expert consensus. An overview of the phases of this study is presented in Fig. 1.

A scoping review was conducted to identify all existing tools and items, and to assess these in terms of the extent to which they are inclusive of social realities that shape Indigenous health [55, 78]. The review determined that no existing tools are broadly suitable to the needs of Indigenous patients and that existing concepts within many tools need heavy contextualization in order to effectively assess complexity among Indigenous patients [55]. To identify additional domains and concepts of complexity, nine urban Indigenous patients (seven females, two males) were recruited to participate in semi-structured relational conversations with AS to explore the factors contributing to health complexity (see Appendix A for interview guide). Participants were from diverse Indigenous backgrounds but resided in [namewithheld] region where this study took place. The interview guide was pre-tested with the research team (RH, AM, LC, and CB) prior to data collection. Interview data was co-coded with an Indigenous health expert to ensure findings would be culturally sensitive and respect the perspectives of Indigenous peoples. Data was further refined with the research team. Adversity arising from material resources and healthcare interactions were identified as sources of health complexity that elicit psychological responses among patients [56]. Drivers of resilience and other protective factors were also identified that work to prevent health complexity [56]. A targeted search based on additional factors identified through the patient interviews was conducted to identify pre-existing instruments that assess these additional domains to further populate the candidate item pool.

Refinement and contextualization of framework and candidate item pool

Based on synthesized knowledge from the scoping review and the patient interview study, the third phase of the study outlined here aims to (a) contextualize the most significant emergent concepts to better align with the realities of Indigenous patients; (b) remove redundant items from the pool of candidate items (i.e., concepts and queries for potential inclusion in an Indigenous-focused PCAT); and (c) modify existing items within the concepts in the candidate item pool to better reflect the needs of Indigenous patients. This was done by AS, LC, and CB. Concepts were contextualized (see Table 1) by leveraging a constructivist paradigm [79,80,81] and building upon the experiences of both LC and CB in their clinical practice with Indigenous patients [82]. This was an iterative, reflective, and time-intensive process which consisted of five meetings over the course of 4 months to review an item pool of over 300 items.

Redundancy was common within the item pool as several items asked the same questions but with phrasing variations; therefore, these were merged into one item when duplicated. For example, many items asked “what is your age?” or “please indicate your age,” – these were merged into a single item that upheld its core concept to reduce repetition. Existing items were modified as per established recommendations for adaptations of research instruments [83]; they were also adjusted to keep operational equivalence [84], which refers to items kept within similar formats to their original state, including the measurement scale that was used originally [85]. Broader concepts were adjusted to better suit use with an Indigenous population [78, 86]. For example, we broadened the concept of income which commonly asked the patient how much money they made annually to include considerations of the extent to which their money may be going to support others in their household.

Modified e-Delphi consensus process

The RAND/UCLA appropriateness method [87] was chosen to define the domains and concepts and then refine the item pool. Through a modified e-Delphi consensus process [88,89,90], concepts were verified to be included in an Indigenous-centered complexity framework along with essential items for collecting information about these concepts. To generate input from diverse perspectives, a purposive panel of HCPs, researchers, and policymakers who work within the field of Indigenous health in Alberta, Canada were identified and invited to participate in this phase. Experts were recruited via email to participate in a 3-round modified e-Delphi consensus process [90] carried out over the course of 4 weeks (October 3rd – November 1st, 2022) using the Qualtrics platform for electronic surveys in the following order:

-

1.

Orientation to the modified e-Delphi consensus process

-

2.

Round #1: voting on concepts

-

3.

Provide a report summarizing results and free-text responses

-

4.

Round #2: voting on items

-

5.

Group discussion

-

6.

Provide a report summarizing results and free-text responses

-

7.

Round #3: voting on items again

Honoraria for experts was not provided therefore only those who felt a commitment towards this work participated. The three rounds progressed attention from identifying concepts, to ranking effectiveness, to discussing and reviewing prioritized items. To launch the e-Delphi consensus process, an introductory orientation meeting was held with the panel of experts to provide an opportunity to ask and address any uncertainties about the process. In Round #1, experts rated each of the overarching concepts based on whether or not they should be included in a tool of this nature, ranking these on a scale of 1 (absolutely not) to 9 (absolutely yes). Free-text fields were provided for each concept for experts to submit any additional feedback on the concepts and their definitions. Concepts would have to achieve a median score ≥ 7 from the panel with no disagreement among experts to be carried forward into the next rounds. Median scores were calculated according to the RAND/UCLA appropriateness method handbook [87] and disagreement was defined according to the inter-percentile range adjusted for symmetry [87].

In Round #2, experts were asked to rate each item on a scale of 1 to 9 (as above) based on how effective [91] the item would be in assessing health complexity with Indigenous patients. Prior to completing responses, expert panel participants were provided via a PDF as an email attachment with the group ratings of concepts from Round #1 as well as the anonymous text feedback from others [92, 93]. An added benefit of sharing the collective responses from prior rounds was that experts could consider the subject matter in terms of how their peers made sense of it. As before, free-text fields were provided for experts to submit any additional feedback on the items and their scoring in Round #2. The inclusion of items in the next round also required median scores ≥7 with no disagreement among experts [87].

Following the completion of Round #2, the experts were invited to a two-hour online video-based group discussion to review concepts and items that were scored lower and to revisit any comments indicating uncertainty or dissension recurring within the free-text fields. This meeting was recorded to track important discussion points and make any final changes or clarifications to the wording and/or scoring of the concepts and items. Changes were made in this group discussion session if the experts indicated consensus amongst themselves, defined as no voiced opposition. The sample of experts consisted of a panel who broadly knew and worked with one another at advanced levels, presuming consensus from no voiced opposition was reasonable. Participants were able to express opposition anonymously by reaching out to the lead author directly.

Following this group session, a report was circulated to all healthcare experts highlighting the summary of suggestions and changes made. A third round of voting was conducted, focused on how effective [91] the experts considered items would be if included in such a tool, again on a scale of 1 (not at all) to 9 (completely). Experts were provided with free-text fields to enter any final feedback on the items. To be included in the final item pool, items once again required median scores ≥7 with no disagreement [87].

Ethics

This study was approved by the University of Calgary's Conjoint Health Research Ethics Board, Certification #REB20–0972. All participants in the modified e-Delphi consensus process provided their consent to participate in this study.

Results

Refinement and contextualization of framework and candidate item pool

After refinement of the framework and candidate item pool, a total of 3 concepts within the biological and social domains were eliminated as they were deemed irrelevant in the context of Indigenous patient complexity. Cognition was eliminated as it was subject to the HCP's perception of a patient's cognitive capacity and therefore deemed potentially dangerous within the context of complexity among Indigenous patients. Weight was eliminated as it only provides one aspect of an individual’s body composition. Community was eliminated as it was not inclusive of what ‘community’ includes for Indigenous peoples, which was rather captured in a domain that was added. Domains of adverse life experiences, healthcare violence, and resilience and culture were added (see Table 2). Items within concepts were also separated if they would be completed by the patient or the HCP, see Appendix B.

Modified e-Delphi consensus process

The Delphi panel was comprised of n = 14 experts in Round #1, n = 11 experts in Round #2, and n = 10 experts in Round #3. The research team (AS, CB, LC) did not participate in the Delphi panel. There were seven researchers who work in various domains of Indigenous health, three researchers and policymakers in Indigenous health, and four health service providers, including one community health provider, one family physician, one radiation therapist, and one palliative care physician – all of which had extensive experience working with Indigenous patient populations. Of the panel, five members self-identified as Indigenous. A total of n = 3 experts attended the summative group discussion session including a community health researcher, an Indigenous health social scientist, and a family physician. In Round #1, all concepts were agreed upon to be included in the Indigenous-centered patient complexity framework (see Table 3).

In Round #2, no items were eliminated and all voting members agreed that these items should be included in the proposed Indigenous-centered complexity framework (see Table 4). In the group discussion meeting, items were modified based on wording suggestions and repetitive feedback. One new item was added, which asked whether the patient was a caregiver for someone else for a total of 64 items to be voted on in Round #3. In Round #3, all 64 items met the criteria to be included in the final set of items for an Indigenous-centered PCAT (see Table 4 and Appendix B).

Within comments in the free-text fields provided and during the group discussion, concerns were raised regarding the feasibility of a tool if it were to include all items, given their length and the lack of item reduction that took place during Rounds #2 and #3. Despite an emphasis on reduction during the group discussion and circulated report to experts, all items met the criteria to be included as part of the final tool, demonstrating their importance in assessing complexity among Indigenous patients and stirring possible need for other strategies to help reduce the burden of length.

Discussion

Healthcare systems in Canada are set up in ways that tend to dismiss the colonial history and its ongoing impacts on Indigenous peoples’ health [94, 95]. Current models of healthcare delivery seldom take into account broader determinants of health that influence Indigenous peoples and their well-being, in turn, further perpetuating health inequities [94, 96]. Clinical frameworks can serve as tools to foster a culturally safe environment [97, 98], and respectful dialogue [99, 100] with Indigenous patients to promote shared decision-making [101, 102], honour self-determination in health [103, 104], and arrive at mutually agreed-upon management plans that advance good health while simultaneously honouring Indigenous values [105, 106]. This study describes the development of a framework tailored for use with Indigenous peoples in clinical settings, with the intention that it may eventually serve as a resource for HCPs to engage critical theoretical domains important to complex patient care. The goal of the framework is to provide a categorization of the dimensions that are encompassed within complexity—providing an understanding of why a patient may be present as “complex” in healthcare settings. By purposefully exploring the aspects that all collectively contribute to complexity observed in patient presentations, this framework aims to help HCPs gain insight into the nature of health complexity among Indigenous patients, ultimately promoting their capacity to navigate and address the challenges that arise with health complexity. As the culmination of a multi-phased approach, findings offer a theoretical structure for key domains of complexity shaping Indigenous patient health. The present study explores the sources of complexity and their presentations among Indigenous patients.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) of Canada has called for HCPs to be educated on the impacts of colonialism on Indigenous health, to promote cultural safety and sensitivity in healthcare interactions [23, 78, 107]. HCPs today may not fully understand or perceive the historical and ongoing drivers of poor health that continue to harm Indigenous patients, presenting with an overall lack of awareness that can impact the effectiveness of healthcare delivery [47, 108]. Service innovations that exist at the interface of Indigenous patients and HCPs, such as a patient complexity assessment framework, can be a resource to bridge gaps in understanding contributors to good health for Indigenous patients. This framework could provide comprehensive high-quality care provisions by opening possibilities for addressing social and structural determinants of health within Western biomedical spaces.

For Indigenous peoples, health is inextricably tied to the determinants of health that have arisen from colonization. As outlined in the TRC’s 94 Calls to Action [23], there are many possibilities within the health sector to support reconciliation with Indigenous peoples [109]. The findings of this study are aligned with the directions of reconciliation set out by the TRC Calls to Action [23]. By providing care that is better suited to the needs of Indigenous peoples, we can advance health equity [110,111,112] and diminish the impacts of systemic factors that negatively influence the health of Indigenous peoples. Having appropriate resources, such as an Indigenous-centered patient complexity framework, is a means to foment capacity among HCPs to better engage with Indigenous patients, as well as to acknowledge and act on the insidious role of colonization in shaping health outcomes [113, 114]. HCPs require the awareness and competencies to effectively address complexity among Indigenous patients [107, 113, 115, 116]. The patient complexity assessment framework presented here builds evidence for a potential resource aimed at enabling deeper and more meaningful clinical interactions between HCPs and Indigenous patients. It can help to advance cultural safety in clinical settings which refers to having practices rooted in a basic understanding of Indigenous peoples’ beliefs and history while also engaging a process of self-reflection to understand the power differences between the HCP and patient which can impact the process of care and healing [117]. Not only might the framework provide a lens for HCPs to better discern health determinants stemming from colonization, but it may also enhance the capacity of the HCPs to reconstruct their pathways of care to more effectively address the needs of Indigenous patients. This work supports directions to culturally safe care and leads the way in decolonizing approaches to care.

Strengths and limitations

The framework presented offers HCPs an opportunity to understand the nature and specific origins of the realities that continue to shape the health of Indigenous patients. This knowledge presents an actionable opportunity to shift HCPs’ tendencies to locate blame within the patient for health outcomes to instead locate cause within structural and systemic dynamics arising from inequity as an outcome of colonization. The approach taken to develop this framework is critical and rigorous in how it engages with many disciplines of knowledge, centering Indigenous knowledge throughout the process. The framework holds significant theoretical rigour that provides a strong foundation of knowledge for informing any future PCATs given its multi-phased development and continuous refinement. Furthermore, items developed are highly validated derived from published measures, informed by the lived experiences of Indigenous patients, contextualized to reflect the social realities that shape the health of Indigenous peoples, and reviewed by healthcare experts within the field of Indigenous health.

As noted in the results section, it is limited by the number of items selected to be included in the proposed Indigenous-centered PCAT, risking that such a tool is burdensome to employ in regular clinical practice. Future advancements of this work will employ psychometric methods and experiment with novel delivery approaches in order to reduce the burden of eliciting items and to ensure the tool’s feasibility for use in clinical settings. Considerations of health literacy will also be undertaken in the refinement of the items as many of them may not be easily understood by patients without prior knowledge and/or clear definitions. Within the item pool, there are no items that directly ask about the role of discrimination, racism, stereotyping, and mistrust in perpetuating complexity within the Indigenous patient. While important concepts, the nature of the tool’s employment causes concern to be cautious in alienating the HCPs and creating context that causes discomfort for both the patient and HCP. Likewise, inquiries about systemic inequities may serve to paralyze HCPs, implicitly suggesting that if complexity is caused by structural and institutional factors, HCPs are then incapable of addressing complexity within the Indigenous patient. This is a limitation of the nature of such tools, and future advancements of this research will explore avenues to create safety for such disclosures. A key question remains whether complexity, which is an unobservable construct, exists as a unitary construct or if it represents a collection of correlated facets without a common core [118]. Future analyses will explore the presence of any dimensions within the framework that reflect a global, underlying construct of complexity [ 118]. Another limitation is that both the Indigenous patients who contributed to phase two of this work and the HCPs, policymakers, and researchers who participated in phase four of this work represent the regional area of Alberta, Canada. Future advancements of this work will explore the applicability of such a PCAT outside of this region.

Future steps

While we have presented a framework of Indigenous patient complexity, future steps of this work are aligned with addressing the limitations of this study and will advance the goal of having a PCAT for use in clinical settings. A subsequent PCAT developed from the framework presented here could be used in practice as an initial screening tool to assess new Indigenous patients for complexity or as a longitudinal tool that may be employed across many points throughout the patients’ healthcare journey providing opportunity for comparative analyses to determine changes in complexity. Pilot data will be collected for a factor analysis in a bid to reduce the number of items included in such an Indigenous-centered PCAT [119,120,121]. Using the framework presented as a model of data, we will test hypotheses regarding the number of factors, the correlation between those factors, and the relationship of the items to the factors [119,120,121]. Factors are larger than items and concepts to allow for refining and rendering a more precise tool. Pilot data will also help to inform the best use of the tool, ensuring Indigenous patient needs are being met.

Conclusion

Through the critical application of the integrated concepts presented within the framework, we put forth a set of recommendations to improve clinical care interactions between HCPs and Indigenous patients, advance cultural safety in healthcare settings, and hold space for Indigenous epistemologies and experiences within social and healthcare structures that continue to systemically disadvantage Indigenous peoples. The framework presented here offers an evolving body of knowledge to enhance capacity to inform HCPs, systems, and policies on how to facilitate better health outcomes with Indigenous peoples. Future research will work to reduce the number of items in such a tool to advance usability within clinical settings.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due privacy considerations but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- HCPs:

-

Healthcare providers

- PCATs:

-

Patient complexity assessment tools

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

- TRC:

-

Truth and Reconciliation Commission

References

Willows ND. Determinants of healthy eating in Aboriginal peoples in Canada: the current state of knowledge and research gaps. Canadian J Public Health/Revue Canad de Sante’e Publ. 2005;1:S32–6.

Statistics Canada. Dictionary: 2016 census of population. Ottawa: Statistics Canada; 2017.

Statistics Canada. Aboriginal peoples of Canada: a demographic profile, 2006 census. Ottawa: Statistics Canada; 2006.

Khawaja M. Consequences and remedies of Indigenous language loss in Canada. Societies. 2021;11(3):89.

Von Der Porten S. Canadian Indigenous governance literature: a review. AlterNative: An Int J Indigen Peoples. 2012;8(1):1–4.

Gracey M. Historical, cultural, political, and social influences on dietary patterns and nutrition in Australian Aboriginal children. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;72(5):1361s–7s.

Lancet T. The past is not the past for Canada's Indigenous peoples. Lancet (London England). 2021;397(10293):2439.

Walde D. Sedentism and pre-contact tribal organization on the northern plains: colonial imposition or Indigenous development? World Archaeol. 2006;38(2):291–310.

Crichlow W. Western colonization as disease: native adoption and cultural genocide. Crit Soc Work. 2002;3(1):1–4.

Neu D. Accounting and accountability relations: colonization, genocide and Canada’s first nations. Account Audit Account J. 2000;13(3):268–88.

Jimenez VM. With good intentions: euro-Canadian and Aboriginal relations in colonial Canada. Can Ethn Stud. 2006;38(2):181.

Leach A. The roots of Aboriginal homelessness in Canada. Parity. 2010;23(9):12–3.

Brown HJ, McPherson G, Peterson R, Newman V, Cranmer B. Our land, our language: connecting dispossession and health equity in an Indigenous context. Canadian J Nurs Res Archiv. 2012;1:44–63.

Bombay A, Matheson K, Anisman H. The intergenerational effects of Indian residential schools: implications for the concept of historical trauma. Transcult psychiat. 2014;51(3):320–38.

De Leeuw S. ‘If anything is to be done with the Indian, we must catch him very young’: colonial constructions of Aboriginal children and the geographies of Indian residential schooling in British Columbia. Canada Child Geograph. 2009;7(2):123–40.

Daschuk JW. Clearing the plains: disease, politics of starvation, and the loss of Aboriginal life. University of Regina Press; 2013.

Osterath B. European diseases left their mark on First Nations' DNA. Nat News. 2016;1–2.

Martin K, Mirraboopa B. Ways of knowing, being and doing: a theoretical framework and methods for Indigenous and indigenist re-search. J Aust Stud. 2003;27(76):203–14.

McGuire–Kishebakabaykwe PD. Exploring resilience and Indigenous ways of knowing. Pimatisiwin. 2010;8(2):117–31.

Adelson N. The embodiment of inequity: health disparities in Aboriginal Canada. Can J Public Health. 2005;96(Suppl 2):S45–61.

Kendall J. Circles of disadvantage: Aboriginal poverty and underdevelopment in Canada. Am Rev Can Stud. 2001;31(1–2):43–59.

Richmond CA, Ross NA. The determinants of first nation and Inuit health: a critical population health approach. Health place. 2009;15(2):403–11.

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Calls to Action. Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. 2015.

Stanton K. Reconciling reconciliation: differing conceptions of the supreme court of Canada and the Canadian truth and reconciliation commission. J Law Soc Policy. 2017;26:21.

MacDonald C, Steenbeek A. The impact of colonization and western assimilation on health and wellbeing of Canadian Aboriginal people. Int J Reg Local Hist. 2015;10(1):32–46.

Kubik W, Bourassa C, Hampton M. Stolen sisters, second class citizens, poor health: the legacy of colonization in Canada. Human Soc. 2009;33(1–2):18–34.

Kim PJ. Social determinants of health inequities in Indigenous Canadians through a life course approach to colonialism and the residential school system. Health Equity. 2019;3(1):378–81.

Tjepkema M, Bushnik T, Bougie E. Life expectancy of first nations, Métis and Inuit household populations in Canada. Health Rep. 2019;30(12):3–10.

King M. Chronic diseases and mortality in Canadian Aboriginal peoples: learning from the knowledge. Prev Chronic Dis. 2011;8(1)

Leung L. Diabetes mellitus and the Aboriginal diabetic initiative in Canada: an update review. J Family Med Prim Care. 2016;5(2):259.

Crowshoe L, Dannenbaum D, Green M, Henderson R, Hayward MN, Toth E. Diabetes Canada clinical practice guidelines expert committee. Type 2 diabetes and Indigenous peoples. Can J Diabet. 2018;42:S296–306.

Jacobs K, Gill K. Substance abuse in an urban Aboriginal population: social, legal and psychological consequences. J Ethn Subst Abus. 2001;1(1):7–25.

Callaghan RC, Cull R, Callaghan RC, Cull R, Vettese LC, Taylor L. A gendered analysis of Canadian Aboriginal individuals admitted to inpatient substance abuse detoxification: a three-year medical chart review. Am J Addict. 2006;15(5):380–6.

Hickey S, Roe Y, Ireland S, Kildea S, Haora P, Gao Y, et al. A call for action that cannot go to voicemail: research activism to urgently improve Indigenous perinatal health and wellbeing. Women Birth. 2021;34(4):303–5.

Barnabe C, Jones CA, Bernatsky S, Peschken CA, Voaklander D, Homik J, et al. Inflammatory arthritis prevalence and health services use in the first nations and non–first nations populations of Alberta. Canada Arthrit care res. 2017;69(4):467–74.

Kirmayer LJ, Brass GM, Tait CL. The mental health of Aboriginal peoples: transformations of identity and community. Can J Psychiat. 2000;45(7):607–16.

Montgomery PB, Hall L, Newton-Mathur D, Forchuk C, Mossey S. Sheltering Aboriginal women with mental illness in Ontario, Canada: being “kicked” and nurtured. J Nurs Care. 2014;3(3):1–6.

Laupland KB, Karmali S, Kirkpatrick AW, Crowshoe L, Hameed SM. Distribution and determinants of critical illness among status Aboriginal Canadians. A population-based assessment. J Crit Care. 2006;21(3):243–7.

Axelsson P, Kukutai T, Kippen R. The field of Indigenous health and the role of colonisation and history. J Popul Res. 2016;33:1–7.

Paradies Y. Colonisation, racism and Indigenous health. J Popul Res. 2016;33(1):83–96.

Paradies Y. Racism and Indigenous health. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Global Public Health. 2018. p. 1–21.

Fraser SL, Gaulin D, Fraser WD. Dissecting systemic racism: policies, practices and epistemologies creating racialized systems of care for Indigenous peoples. Int J Equity Health. 2021;20:1–5.

Waterworth P, Pescud M, Braham R, Dimmock J, Rosenberg M. Factors influencing the health behaviour of Indigenous Australians: perspectives from support people. PLoS One. 2015;10(11):e0142323.

Turpel-Lafond ME, Johnson H. In plain sight: addressing Indigenous-specific racism and discrimination in BC health care. BC Stud. 2021;5(209):7–17.

Kitching GT, Firestone M, Schei B, Wolfe S, Bourgeois C, O’Campo P, et al. Unmet health needs and discrimination by healthcare providers among an Indigenous population in Toronto. Canada Canad J Public Health. 2020;111:40–9.

Eni R, Phillips-Beck W, Achan GK, Lavoie JG, Kinew KA, Katz A. Decolonizing health in Canada: a Manitoba first nation perspective. Int J Equity Health. 2021;20(1):1–2.

National Collaborating Centre for Indigenous Health. Access to health services as a social determinant of First Nations, Inuit and Métis health. 2019. Available from: https://www.nccih.ca/docs/determinants/FS-AccessHealthServicesSDOH-2019-EN.pdf.

Hewa S, Hetherington RW. Specialists without spirit: limitations of the mechanistic biomedical model. Theor Med. 1995;16:129–39.

West-McGruer K. There’s ‘consent’ and then there’s consent: Mobilising Māori and Indigenous research ethics to problematise the western biomedical model. J Sociol. 2020;56(2):184–96.

Phillips-Beck W, Eni R, Lavoie JG, Avery Kinew K, Kyoon Achan G, Katz A. Confronting racism within the Canadian healthcare system: systemic exclusion of first nations from quality and consistent care. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(22):8343.

Anderson W. The colonial medicine of settler states: comparing histories of Indigenous health. Health Hist. 2007;9(2):144–54.

Davy C, Harfield S, McArthur A, Munn Z, Brown A. Access to primary health care services for Indigenous peoples: a framework synthesis. Int J Equity Health. 2016;15:1–9.

Nguyen NH, Subhan FB, Williams K, Chan CB. Barriers and mitigating strategies to healthcare access in Indigenous communities of Canada: a narrative review. Healthcare. 2020;8(2):112.

Hole RD, Evans M, Berg LD, Bottorff JL, Dingwall C, Alexis C, et al. Visibility and voice: Aboriginal people experience culturally safe and unsafe health care. Qual Health Res. 2015;25(12):1662–74.

Sehgal A, Barnabe C, Crowshoe L. Patient complexity assessment tools containing inquiry domains important for Indigenous patient care: a scoping review. PLoS One. 2022;17(8):e0273841.

Sehgal A, Scott S, Murry A, Henderson R, Barnabe C, Crowshoe L. Exploring health complexity with urban Indigenous peoples for healthcare equity: a qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2023;13(10):1–9.

Knibb-Lamouche J. Culture as a social determinant of health. In: Commissioned paper prepared for the institute on medicine, roundtable on the promotion of health equity and the elimination of health disparities. 2012.

Smylie J, Firestone M. The health of Indigenous peoples. Social Determ Health Canad Perspect. 2016;6:434–69.

Peek CJ, Baird MA, Coleman E. Primary care for patient complexity, not only disease. Famil Syst Health. 2009;27(4):287.

Loeb DF, Bayliss EA, Candrian C, deGruy FV, Binswanger IA. Primary care providers’ experiences caring for complex patients in primary care: a qualitative study. BMC Fam Pract. 2016;17(1):1–9.

Ben-Menahem S, Sialm A, Hachfeld A, Rauch A, von Krogh G, Furrer H. How do healthcare providers construe patient complexity? A qualitative study of multimorbidity in HIV outpatient clinical practice. BMJ Open. 2021;11(11):e051013.

Nicolaus S, Crelier B, Donzé JD, Aubert CE. Definition of patient complexity in adults: a narrative review. J Multimorbid Comorbid. 2022;17(12):26335565221081288.

Mount JK, Massanari RM, Teachman J. Patient care complexity as perceived by primary care physicians. Famil Syst Health. 2015;33(2):137.

Webster F, Rice K, Bhattacharyya O, Katz J, Oosenbrug E, Upshur R. The mismeasurement of complexity: provider narratives of patients with complex needs in primary care settings. Int J Equity Health. 2019;18(1):1–8.

Kaneko H, Hanamoto A, Yamamoto-Kataoka S, Kataoka Y, Aoki T, Shirai K, et al. Evaluation of complexity measurement tools for correlations with health-related outcomes, health care costs and impacts on healthcare providers: a scoping review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(23):16113.

Bodenheimer T, Berry-Millett R. Care management of patients with complex health care needs. Policy. 2009;1(6):1–6.

Latour CH, Huyse FJ, De Vos R, Stalman WA. A method to provide integrated care for complex medically ill patients: the INTERMED. Nurs Health Sci. 2007;9(2):150–7.

Pratt R, Hibberd C, Cameron IM, Maxwell M. The patient centered assessment method (PCAM): integrating the social dimensions of health into primary care. J Comorbid. 2015;5(1):110–9.

Schaink AK, Kuluski K, Lyons RF, Fortin M, Jadad AR, Upshur R, et al. A scoping review and thematic classification of patient complexity: offering a unifying framework. J comorbid. 2012;2(1):1–9.

De Jonge P, Huyse FJ, Slaets JP, Söllner W, Stiefel FC. Operationalization of biopsychosocial case complexity in general health care: the INTERMED project. Austral New Zealand J Psychiat. 2005;39(9):795–9.

Reuben DB, Keeler E, Seeman TE, Sewall A, Hirsch SH, Guralnik JM. Development of a method to identify seniors at high risk for high hospital utilization. Med Care. 2002;1:782–93.

Wallace E, McDowell R, Bennett K, Fahey T, Smith SM. External validation of the probability of repeated admission (Pra) risk prediction tool in older community-dwelling people attending general practice: a prospective cohort study. BMJ Open. 2016;6(11):e012336.

Wild B, Heider D, Maatouk I, Slaets J, König HH, Niehoff D, et al. Significance and costs of complex biopsychosocial health care needs in elderly people: results of a population-based study. Psychosom Med. 2014;76(7):497–502.

Pacala JT, Boult C, Boult L. Predictive validity of a questionnaire that identifies older persons at risk for hospital admission. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1995;43(4):374–7.

Peters LL, Burgerhof JG, Boter H, Wild B, Buskens E, Slaets JP. Predictive validity of a frailty measure (GFI) and a case complexity measure (IM-E-SA) on healthcare costs in an elderly population. J Psychosom Res. 2015;79(5):404–11.

Yoshida S, Matsushima M, Wakabayashi H, Mutai R, Sugiyama Y, Yodoshi T, et al. Correlation of patient complexity with the burden for health-related professions, and differences in the burden between the professions at a Japanese regional hospital: a prospective cohort study. BMJ Open. 2019;9(2):e025176.

Horrill T, McMillan DE, Schultz AS, Thompson G. Understanding access to healthcare among Indigenous peoples: a comparative analysis of biomedical and postcolonial perspectives. Nurs Inq. 2018;25(3):e12237.

Crowshoe LL, Henderson R, Jacklin K, Calam B, Walker L, Green ME. Educating for equity care framework: addressing social barriers of Indigenous patients with type 2 diabetes. Can Fam Phys. 2019;65(1):25–33.

Adom D, Yeboah A, Ankrah AK. Constructivism philosophical paradigm: implication for research, teaching and learning. Global j arts human soc sci. 2016;4(10):1–9.

Lee CJ. Reconsidering constructivism in qualitative research. Educ Philos Theory. 2012;44(4):403–12.

Kamal SS. Research paradigm and the philosophical foundations of a qualitative study. PEOPLE. Int J Soc Sci. 2019;4(3):1386–94.

Burns M, Bally J, Burles M, Holtslander L, Peacock S. Constructivist grounded theory or interpretive phenomenology? Methodological choices within specific study contexts. Int J Qual Methods. 2022;7(21):16094069221077758.

Gjersing L, Caplehorn JR, Clausen T. Cross-cultural adaptation of research instruments: language, setting, time and statistical considerations. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2010;10:1.

Reichenheim ME, Moraes CL. Operationalizing the cross-cultural adaptation of epidemological measurement instruments. Rev Saude Publica. 2007;41:665–73.

Herdman M, Fox-Rushby J, Badia X. A model of equivalence in the cultural adaptation of HRQoL instruments: the universalist approach. Qual Life Res. 1998;7:323–35.

Cook DA, Beckman TJ. Current concepts in validity and reliability for psychometric instruments: theory and application. Am J Med. 2006;119(2):166–e7.

Fitch K, Bernstein SJ, Aguilar MD, Burnand B, LaCalle JR, Lazaro P, et al. The RAND/UCLA appropriateness method user’s manual. Santa Monica: RAND Corporation; 2001.

Donohoe H, Stellefson M, Tennant B. Advantages and limitations of the e-Delphi technique: implications for health education researchers. Am J Health Educ. 2012;43(1):38–46.

Rowe G, Wright G, Bolger F. Delphi: a reevaluation of research and theory. Technol Forecast Soc Chang. 1991;39(3):235–51.

Hsu CC, Sandford BA. The Delphi technique: making sense of consensus. Pract Assess Res Eval. 2007;12(1):10.

Health Quality Council of Alberta. The Alberta Quality Matrix for Health. 2005. Available from: https://hqca.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/HQCA_11x8_5_Matrix.pdf.

Vernon W. The Delphi technique: a review. Int J Ther Rehabil. 2009;16(2):69–76.

Humphrey-Murto S, Varpio L, Wood TJ, Gonsalves C, Ufholz LA, Mascioli K, et al. The use of the Delphi and other consensus group methods in medical education research: a review. Acad Med. 2017;92(10):1491–8.

Boyer Y. Healing racism in Canadian health care. CMAJ. 2017;189(46):E1408–9.

Burnett K, Sanders C, Halperin D, Halperin S. Indigenous peoples, settler colonialism, and access to health care in rural and northern Ontario. Health Place. 2020;1(66):102445.

Kolahdooz F, Nader F, Yi KJ, Sharma S. Understanding the social determinants of health among Indigenous Canadians: priorities for health promotion policies and actions. Glob Health Act. 2015;8(1):27968.

Nguyen HT. Patient centred care: cultural safety in Indigenous health. Aust Fam Phys. 2008;37(12).

Greenwood M, Lindsay N, King J, Loewen D. Ethical spaces and places: Indigenous cultural safety in British Columbia health care. AlterNative. 2017;13(3):179–89.

Hovey RB, Delormier T, McComber AM, Lévesque L, Martin D. Enhancing Indigenous health promotion research through two-eyed seeing: a hermeneutic relational process. Qual Health Res. 2017;27(9):1278–87.

Maar M, Yeates K, Barron M, Hua D, Liu P, Lum-Kwong MM, et al. I-RREACH: an engagement and assessment tool for improving implementation readiness of researchers, organizations and communities in complex interventions. Implement Sci. 2015;10(1):1–3.

Groot G, Waldron T, Barreno L, Cochran D, Carr T. Trust and world view in shared decision making with Indigenous patients: a realist synthesis. J Eval Clin Pract. 2020;26(2):503–14.

Jull J, Giles A, Boyer Y, Lodge M, Stacey D. Shared decision making with Aboriginal women facing health decisions: a qualitative study identifying needs, supports, and barriers. AlterNative: An Int J Indigen Peoples. 2015;11(4):401–16.

Auger M, Howell T, Gomes T. Moving toward holistic wellness, empowerment and self-determination for indigenous peoples in Canada: can traditional Indigenous health care practices increase ownership over health and health care decisions? Can J Public Health. 2016;107:e393–8.

Black K, McBean E. Increased Indigenous participation in environmental decision-making: a policy analysis for the improvement of Indigenous health. Int Indigen Policy J. 2016;7(4).

Allen L, Hatala A, Ijaz S, Courchene ED, Bushie EB. Indigenous-led health care partnerships in Canada. Cmaj. 2020;192(9):E208–16.

Dwyer JM, Lavoie J, O’Donnell K, Marlina U, Sullivan P. Contracting for Indigenous health care: towards mutual accountability. Aust J Public Adm. 2011;70(1):34–46.

Towle A, Godolphin W, Alexander T. Doctor–patient communications in the Aboriginal community: towards the development of educational programs. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;62(3):340–6.

Anderson MJ, Smylie JK. Health systems performance measurement systems in Canada: how well do they perform in first nations, Inuit, and Métis contexts? Pimatisiwin. 2009;7(1):99.

McNally M, Martin D. First nations, Inuit and Métis health: considerations for Canadian health leaders in the wake of the truth and reconciliation Commission of Canada report. Healthc Manage Forum. 2017;30(2):117–22.

Browne AJ, Varcoe C. Critical cultural perspectives and health care involving Aboriginal peoples. Contemp Nurse. 2006;22(2):155–68.

Tookenay VF. Improving the health status of Aboriginal people in Canada: new directions, new responsibilities. CMAJ. Can Med Assoc J. 1996;155(11):1581.

Beavis AS, Hojjati A, Kassam A, Choudhury D, Fraser M, Masching R, et al. What all students in healthcare training programs should learn to increase health equity: perspectives on postcolonialism and the health of Aboriginal peoples in Canada. BMC Medic Educ. 2015;15(1):1–11.

Kerrigan V, Lewis N, Cass A, Hefler M, Ralph AP. “How can I do more?” cultural awareness training for hospital-based healthcare providers working with high Aboriginal caseload. BMC Medic Educ. 2020;20:1–11.

Wilson AM, Kelly J, Jones M, O’Donnell K, Wilson S, Tonkin E, et al. Working together in Aboriginal health: a framework to guide health professional practice. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):1–11.

Wilson D, de la Ronde S, Brascoupé S, Apale AN, Barney L, Guthrie B, et al. Health professionals working with first nations, Inuit, and Métis consensus guideline. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2013;35(6):S1–4.

Macaulay AC. Improving Aboriginal health: how can health care professionals contribute? Can Fam Phys. 2009;55(4):334–6.

Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada. Indigenous values, health and principles statement. The Indigenous Health Advisory Committee and the Office of Health Policy and Communications. 2013. Available from: http://www.royalcollege.ca/portal/page/portal/rc/common/documents/policy/indigenous_health_values_principles_report_e.pdf.

Morin AJ, Arens AK, Tran A, Caci H. Exploring sources of construct-relevant multidimensionality in psychiatric measurement: a tutorial and illustration using the composite scale of Morningness. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2016;25(4):277–88.

Orçan F. Exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis: which one to use first? J Measure Evaluat Educ Psychol. 2018;9(4):414–21.

Thompson B. Exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis: understanding concepts and applications. Washington DC: American Psychological Association; 2004.

Hurley AE, Scandura TA, Schriesheim CA, Brannick MT, Seers A, Vandenberg RJ, et al. Exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis: guidelines, issues, and alternatives. J Organ Behav. 1997;1:667–83.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

None to report.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AS, CB, and LC led the conception, design, data analysis, interpretation, and writing of this manuscript. AM and RH supported equally to the interpretation and writing of this manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval and consent to participation

This study was approved by the University of Calgary’s Conjoint Health Research Ethics Board, Certification #REB20–0972. The study was carried out according to the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants in the modified e-Delphi consensus process provided implied informed consent to participate in this study.

Consent to publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Sehgal, A., Henderson, R., Murry, A. et al. Advancing health equity for Indigenous peoples in Canada: development of a patient complexity assessment framework. BMC Prim. Care 25, 144 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-024-02362-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-024-02362-z